War rations

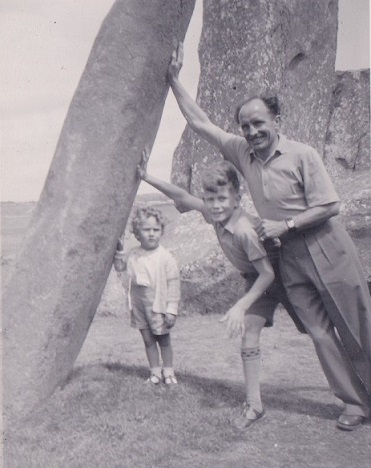

During the war, children were given "orange" juice and hateful cod liver oil, paid for by the government. When the war was over, exotic foods like bananas made their appearance. One teatime at "The Birches", my cousin Ray, told to eat his bread and butter, cried when he found he didn't have room for his banana.During the war, my father was stationed at one time at an airfield in Sunderland, and got to know the Barkers, who lived nearby. After the war, a friend of the Barkers, who was first officer on the liner Queen Mary, showed my father and me over the huge ship, while it was in dry dock in Southampton. After the tour, we had a meal in the first-class dining room. My father had on his plate the biggest piece of meat I had ever seen (more than we got in a week's rations during the war).

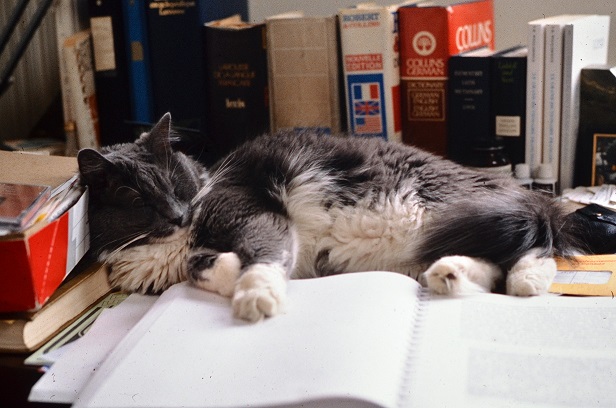

Tiggy

At school, in the South of England, we played a number of games, including he (tag in most countries), relievio, conkers, marbles, jacks (or fivestones), each in its season.One day, when I was about nine, and visiting my grandparents in the Yorkshire West Riding mining town of Maltby, the boy next door asked me: "Dost tha play tiggy?". I was used to the North of England use of the old second person singular pronouns and verb forms, which had long disappeared in the South, and could understand his regional pronunciation of "play"; it was the word "tiggy" that I didn't understand ("Do you play tiggy?"). I quickly gathered that he was referring to the game "he".

My cousin Anthony introduced me to the variant game of kingy, played with a tennis ball and dustbin lids as shields, in the back alleys of the Maltby Crags neighbourhood where he lived.

Comics

I was an avid consumer of British comics in my early teens (and late pre-teens). Since they were "too common", I wasn't allowed to buy The Beano (Pansy Potter) or The Dandy (Desperate Dan and Aunt Aggie), but read borrowed issues. I also read borrowed copies of Radio Fun (Jimmy Jewel and Ben Warriss) and Film Fun (George Formby). I was, however, allowed to receive at home The Eagle (Dan Dare and Digby) and Lion.Then onto story comic papers. There were four to choose from, as I remember: The Wizard, The Hotspur, The Rover, Adventure. The one I favoured was The Wizard. I read it surreptitiously in class, jamming it with my knee against the underside of my desk if the master came round (I managed to escape detection). I revelled in the adventures of Limp Along Leslie and the great Wilson (cf. "Trust and obey").

Finally I left the world of comics to pass into that of novels. The first I remember were The White House Boys and Quo Vadis.

Trust and obey

My Mum's brother Stan worked for the Colonial Service in Nigeria, overseeing the construction of wells. He was very good-looking, with mischievous blue eyes, a hearty chuckle, and a happy-go-lucky attitude to life. He referred to the local Nigerians as "the heathens". He married Dorothy, an unattractive complainer, and the daughter of Mr. Scott.Mr. Scott was a Methodist local preacher. He was a fierce-looking man, whose upper lip was adorned with a brush moustache which looked as if it was built to sweep all before it into hell. His sermons were of the fire-and-brimstone type, causing me to switch off and imagine I was either the great Wilson or Limp Along Leslie of Wizard fame, playing for England at cricket or football, scoring goals, taking wickets and hitting sixes.

Mr. Scott's services inevitably included the poorly written and scored hymn "Trust and obey".

Camping

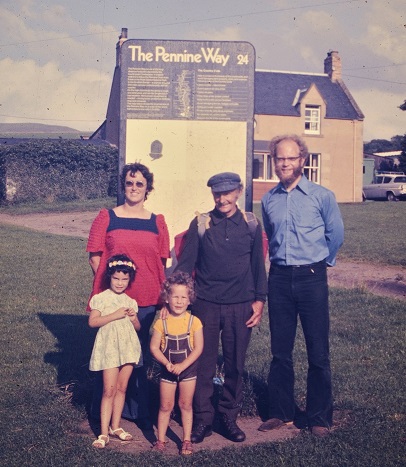

When I was nine, a wolf cub pack was started at St Peter's Hall at Maybush Corner. Then, and later, when I moved up to the boy scout troop, we went camping for a week or a weekend at the end of the spring and each summer: on the Isle of Wight, the banks of the River Test, or in the New Forest, and further afield to Weymouth and the Wye Valley in Wales.

When I was nine, a wolf cub pack was started at St Peter's Hall at Maybush Corner. Then, and later, when I moved up to the boy scout troop, we went camping for a week or a weekend at the end of the spring and each summer: on the Isle of Wight, the banks of the River Test, or in the New Forest, and further afield to Weymouth and the Wye Valley in Wales.

The weekly meetings in St Pater's Hall involved, among other things, dib-dib-dibbing Akela, learning knots and playing the uniform-destroying game of British bulldog. We also went on wide games in the woods at Rownhams. But it was the camping that we all looked forward to. We would load the camping gear and ourselves onto the back of an open lorry and off we went.

Memories: catching wasps in jam-jars in the camp kitchen; earning a badge for making twist, i.e. toasting over a wood fire dough, made from flour and water, wrapped around a hazel stick (this was meant to be a survival skill, but where was one to find flour when lost in the wild?); cutting my thumb while peeling potatoes; singing songs around the camp fire; seeing a test match between England and Australia on a black-and-white television set in a shop window in Brecon (it was Coronation Year, 1953); regurgitating baked beans eaten straight from the tin; getting washed out by the incessant rain; swimming in the Test with May flies.

An inevitable activity after "lights out": telling scary ghost stories in the patrol tent. One morning, Robert Smith was found outside the tent in his dew-drenched sleeping bag, having wriggled under the tent flaps.

Most scouts were C of E. In the Wye Valley, one of the scout leaders was Methodist. On the Sunday, he was to lead the service at the local chapel. One of his hosts lent him a tractor on which he drove Methodist me and another scout to a farmhouse, where we sat around a huge table bearing the most scrumptious spread I had ever seen: bread-and-butter, jams, cakes of all sorts. I remember the tea, but not the following church service.

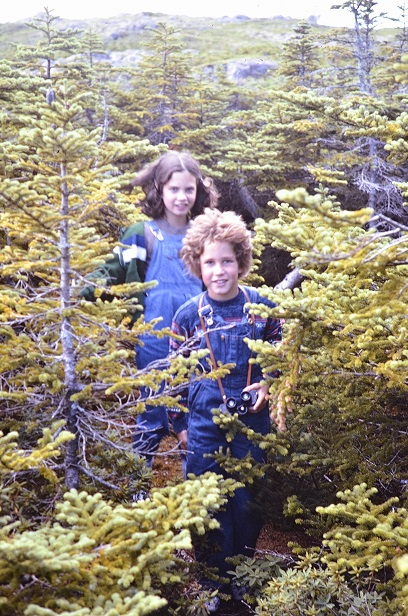

Many years later, my eldest daughter went to a guide camp with her cousin's troop in a field on Pendle Hill (see above), of witchcraft fame. She hated the cold, the wet, and particularly the numerous cow pats. I accompanied my son's beaver colony on a weekend camping trip in Ontario. We all got very muddy from playing soccer in the camp field, but slept, not in tents, but in a luxurious (and dry) hut. I was very fortunate in that my turn to sleep in the same hut as the boys was the second night; the unfortunate men who spent the first night with the boys were kept awake by various pranks, stories and noises coming from the excited beavers. The boys were exhausted by the second night, and went to sleep straightaway!

Sign language and texting

When I was 13, Judy and I attended Senior Sunday School, Judy with the girls, I with the boys. Judy and I would talk to each other via sign language (Judy started it). Pointing at self = "I"; index fingers held apart = "long"; two fingers held up = "to"; counting letters on fingers - 2nd letter = "be"; hands clasped together = "with"; pointing at other = "you". This was a precursor of "LOL" texting.Hello

I was shy of girls. I had no sister, although I was convinced that it was a girl that Mum was carrying when she had a miscarriage during the War.Young people's socials held at St Peter's Hall involved quicksteps, foxtrots and waltzes. Nothing would have induced me to attend.

Then I discovered square dancing. At the Hedgend Methodist youth club I learned the rudiments of do-si-do and The Lancers. It felt "safe".

St Peter's Hall announced the holding of a square dance evening. I felt emboldened enough to attend. On the fateful evening, it was announced that the caller was unwell, and that subsequently the evening would consist of... quicksteps, foxtrots and waltzes. I spent the evening miserably turning pages for Mr Smith at the piano.

Afterwards I felt that the situation had become ridiculous. If Michael Moody and Roger Hannah could dance with girls, why couldn't I?

And so, one morning, instead of catching the train to school, I walked up the Calvary-like hill from the railway station to Southampton High Street, and positioned myself in a strategic spot past which many people had to go on their way to work.

Whenever a young girl went by me, I smiled and wished her a good morning. Some girls hurried past, but about half of them smiled and said hello.

After about twenty minutes, I was exhausted. I descended the hill to the station and caught a train to school in Winchester, a smile on my face.

I never attended another social evening at St Peter's Hall, but I did learn how to do the quickstep, the foxtrot and the waltz. I took a girl to the school sixth-form dance.

Harry

Harry Hawkins was a maths master at Peter Symonds School in Winchester. He was tall and gangling, probably in his forties or fifties. His main claim to fame amongst the boys was this: he could be hypnotised by a swinging light. The classrooms were lit by electric lights on long flexes hanging from the high ceiling. If Harry saw a swinging light, so the story went, his eyes glazed over, his grasping hands would shoot out, and he would walk straight through the intervening desks to the source of attraction, there to still it.His fame amongst the boys was enhanced one mid-morning break while he was supervising the installation in the assembly hall of the crates containing 1/3-pint bottles of milk (a practice later ended by Margaret Thatcher "milk snatcher" while serving as Minister of Education). Harry was bending over. Lewis, one of the school idiots and a born loser in life, mistaking him for a friend, put his hand between Harry's legs, and grabbed his balls.

In the Middle Fifth year we had Harry as our maths master. Doubtless like our predecessors down the years, we one day put the legendary story to the test. Sure enough, Harry's eyes protruded from his head, his arms shot out with grasping hands, and desks were scattered left and right as he strode towards the swinging light bulb.

Terry's older sister, Heather, attended Brockenhurst Grammar School, where she managed to get her hands on a copy of the teacher's edition of the maths textbook we were using. The teacher's edition had all the answers at the back, so all we had to do, on the train taking us to school, was work backwards from the answer to provide the reasoning.

Harry was convinced he knew someone with the same surname as mine, someone who therefore must be related to me, someone he liked. I took advantage of this misconception to keep in Harry's good books. I was good at maths, but even so was surprised to get a term mark of 108%.

The Valentine Card

His name was Robin, but, because his last name was Barton, everyone at school called him Dick, in honour of the radio superhero who had kept us enthralled during our primary school years. He was shy of girls, but none of us boys would be seen dead in the same carriage as the girls travelling from Southampton to Winchester High. We spent the time in the train comparing, or completing, our maths or Latin homework assignments.Dick's main interest was music, his catholic tastes ranging from Brahms to the Everly Brothers. He had, however, mentioned having a soft spot for a girl called Susan, who, like him, lived in Bursledon.

It was January. In the 1950s Saint Valentine had the same status as Cupid or Eros. Class valentines did not, could not, exist. A Valentine card had the potency of Cupid's bow.

And so, unbeknownst to Dick, we hatched a plan. Dick was going to receive a Valentine card from Susan. Vic, who also lived in Bursledon, had a sister. She was going to be Susan, writing, in her girl's hand, an ambiguous message inside a Valentine card, the envelope of which would bear the postmark of Bursledon. Anonymity was a prerequisite for Valentine cards. The recipient of this potent symbol was meant to imagine, wonder and suffer - after all, Cupid's bow shot a wounding arrow.

The card was duly sent and received. It gave us a great deal of fun and satisfaction, Dick appearing at the train in a flustered state on St Valentine's Day. Yet we never let on. We never learned whether Dick approached Susan.

Boarding school

Let me state at the outset that I never went to boarding school, thank goodness. My parents, like every adult I came into contact with when I was a boy, had neither the money nor the social pretensions to think of sending their offspring away for their education.My reason for writing about this subject comes, nevertheless, from my contact with boarders, and a growing horror coming particularly from the accounts of many sufferers, such as that of Rose Tremain in her autobiography Rosie.

My contact came when I attended Peter Symonds grammar achool. About one quarter of the boys were boarders, their school house being called Symonds House, named after the founder of the school. The rest of the boys were assigned geographically to one of three other houses: Kirby (Winchester and nearby), Mackenzie (Eastleigh area) or Northbrook (Southampton region), each named for a benefactor of the school.

The school was run along the lines of a public school. The classes were called forms; the slow boys destined to go no further than 'O' levels were put, in second year, into Remove. The teachers were called masters. The school week comprised full days on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday, and half days on Wednesday and Saturday. The school was in the Public School Yearbook, and the headmaster attended the Headmasters' Conference.

The various internal sporting events were usually won by boarders or by Symonds House. I was particularly pleased, when playing on the top board for the school chess team, to beat my opponent when playing against Winchester College.

School dinners

In primary school, I went home at midday, so I ate the meal prepared for me by my mother. When I went to grammar school, I was travelling, by train, from Southampton to Winchester, so school dinners became a fact of life.Dinner money (for the week) was collected at the beginning of Monday lessons. I remember this particularly in my second year at grammar school, in Form 4B. (The "bright" boys were distributed alphabetically by surname between 4A and 4B; the not so bright were consigned to 4C, the "Remove" form.) Our form master, in whose classroom the roll was called and dinner money collected, was "Biffer" Smith, the junior maths master.

Only masters and prefects were allowed to walk across the field to the cafeteria. We unwashed masses, the hoi polloi of the school, had to walk round by road, caps on, to join the queue, which was policed by prefects.

Once inside and at the counter, the dinner ladies put on our trays a plate loaded with something savoury (meat, potatoes and some sort of vegetable - usually cabbage - cooked to within an inch of extinction) and a second plate containing something sweet (usually a dollop of suet pudding or spotted dick, when varied with raisins or currants). I discovered later that the latter pudding is called "dead baby" elsewhere (Kay knew it by that name). A discussion of Cambridgeshire school slang in Andrew Taylor's An Old School Tie: "'Dead baby,' he explained 'was boiled baby injected with red death. That's to say, steamed suet pudding to which a small quantity of raspberry-flavoured jam had been added [...]'".

In a word, school dinners = stodge, at least in those days.

Vive la différence

A number of us went to Paris for the 10-day Sixth-Form Conference organised during the Easter holidays by the British and French governments. Our stay included attending a lecture in a Sorbonne amphitheatre, attending a reception at the Hôtel de Ville, going up the Tour Eiffel, and visiting Versailles.The boys were housed at the Collège Stanislas, which Charles de Gaulle had attended. On the tables in the refectory were bottles of cider and baskets of baguette slices, neither of which were to be found in British schools.

It was during this stay, my first in France, that I discovered that wine, though made from grapes, did not taste like grape juice.

Our French master, Fluebrush (he had a crew cut) Smith, was married to a Frenchwoman. One summer, Tony and I found ourselves working in the Marne region on a farm run by Fluebrush's sister-in-law and husband.

On the morning of 15th August, the farmer announced that it was a holiday, and we would be spending the day in the nearby village where his father had a farm.

C. of E. Tony and Methodist I were flummoxed. What was so special about the fifteenth day of August? We were none the wiser when we were told it was the feast day of the Assumption of the Virgin. We had only heard of the virgin birth from the Gospels, where there was no mention of Jesus's mother ascending to heaven.

We arrived in the father's village and went straight to church. I thought our farmer showed irreverence by spending a lot of time gazing at a mouse trap which had been laid on the church floor. At the end of the incomprehensible mass, the members of the congregation filed up to the front of the church to kiss a crucifix bearing a crucified Christ held by the priest. Tony and I thought this barbaric and left the church without kissing the crucifix.

My disarray was complete when we went from church to café where alcoholic apéritifs were consumed and the young people playing babyfoot were introduced as brothers, sisters and in-laws of our farmer.

After a Gargantuan three-hour meal, which included a delicious omelette, consumed by the large extended family seated around the huge kitchen table of the father's farm, Tony and I accompanied about four of our farmer's young relatives, male and female, to visit the champagne cellars in nearby Épernay.

When we stopped at a level crossing, our male driver got out of the car and urinated against a tree only a few feet away. I felt embarrassed, particularly as there were ladies present.

On our return, before another marathon meal consumed round the kitchen table, we were taken on a tour of the farm. In one barn, we came across our farmer's little daughter urinating in the straw. In another it was the father relieving himself.

On the way back, our heads, Tony's and mine, were reeling from the day's events. In the years that followed, I became a lot less Methodist, and a lot more appreciative of French culture, both rural and urban.

We were in France, not only for the culture, but also, of course, for the language. We learned a lot from our farmer's two small children, a girl and a boy.

We also went to the cinema to learn. The two of us walked on two Saturdays from the farm to the nearby small town of Montmirail, where in a barn there took place once a week the projection of films to the delight of young and old seated - or not - on benches. We had been told to arrive well in advance of the announced time. It soon became obvious to us that this was above all a social occasion, an opportunity for what seemed to be a good part of the population to catch up on gossip. The feature film was just an excuse.

It was important to us, however. I didn't understand a thing about the first film, but, the second time we went, I was delighted to realise that I could follow what was going on in the hospital.

The main aim of many students in the late 1950s and early 1960s was to get as far away as possible from their parents and learn to grow up. In my case this included pub crawls and collecting souvenirs. For example, to celebrate my 20th birthday Bill and I went from pub to pub and ended up pinching a triple-punned poster entitled "Here the belles peel" from outside the Hulme Hip.

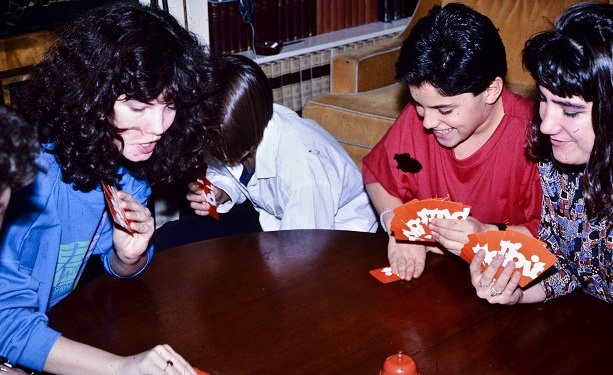

Rag Week was, on the one hand, a week of collecting for charity, and, on the other, an excuse for university students to run wild. The highlights were the Rag Day parade and the Rag Ball. French Soc had the great honour of being able to include the Fresher Queen. Our float featured pretty Jenny seated on a throne dressed in top and tails. The rest of its occupants were boys with faces made up with mascara, rouge and scarlet lipstick and dressed in grass skirts. Its banner bore the proud boast "Vive la différence".

The parade took place in the centre of Manchester. The floats left from the Students' Union with the avowed intent of collecting for charity (we had collection tins), and the unofficial aim of collecting as many office girls as possible by our jumping off, seizing them and putting them (they were quite willing) on the float. French Soc's impressive haul of girls were then treated to coffee back at the Union.

After my second year at university, instead of going into final year I spent a year in a French lycée as an English assistant. I wanted French to exist in my heart and my gut as well as in my head.

After my second year at university, instead of going into final year I spent a year in a French lycée as an English assistant. I wanted French to exist in my heart and my gut as well as in my head.

At the beginning of my final year at Peter Symonds the headmaster had told me that if I wanted to be a prefect I would have to shave off the beard which I had grown over the summer. At the Lycée Alain, several boys had beards.

I spent the year in Alençon drinking cognac, learning slang (argot) from Alfred, keeping the score when we played cards, watching rugby matches (as important to the French as soccer), playing French billiards (no pockets), doing French crossword puzzles, going to the cinema (Brigitte Bardot, Bourvil, Jean Gabin), and going out with French girls (pillow talk is appositely termed in French "apprendre sur l'oreiller").

I also learned a few things about Norman culture. Janine took me to visit a relative who was a farmer in the département of Calvados. Calvados has the privilege of having the highest percentage in France of mentally deficient inhabitants, owing to the abuse of the eponymous apple brandy. This farmer, like many of his peers, made his own (very strong) calvados, awoke his senses each morning through the expedient of dabbing calvados on his face, and kept quiet the many babies which he imposed on his wife by putting a drop of calvados in their bottles. The palate is cleansed between courses of a meal typically by the swallowing of a trou normand, a small glass of calvados. To the espresso coffee consumed at the end of a special meal are added a few drops of calvados; after a few sips, more calvados is added, until one is drinking calvados with a slight flavour of coffee.

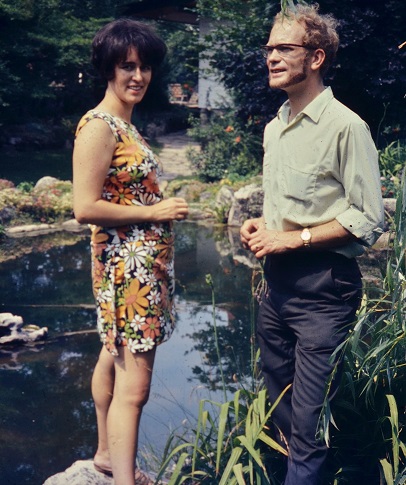

At the beginning of the summer, Janine and I went on my scooter to St Malo to meet my parents, who came over from their holiday in nearby Jersey celebrating their silver wedding. We took them to dinner at the Faisan d'Or, where we managed to introduce them to wine.

Over the summer, I was taken on at the Monuments Historiques office in Caen as English guide at the Abbey of Mont-St-Michel. I quickly learned the patter and the necessity of building up to a climax ending with a flowery statement that my only monetary recompense was visitors' tips (true - guided tours of monuments in Britain did not include tipping).

The real test for me, however, was on 14th July (national holiday) and the famous 15th August, when the number of French visitors was in the thousands. Visits in English were abandoned as all the guides had to pitch in and take a couple of hundred French speakers through the abbey.

At the end of the year, I returned to England with the experience of dreaming in French, the ability to tell a joke in French, and that of spontaneously coming out with expletives like merde alors. Final year was a breeze.

The final stage of my acculturation, the refinement of my palate, took place in Besançon, in the East of France, where I spent three years in between Manchester and emigration to Canada studying for a doctorate.

In Britain at the time, the aim of cooking food seemed to be the killing of harmful substances; the aim of French cooking was, and remains, to bring out flavours. To take the example of the pea (petit pois), many Britons profess a liking for mushy peas; the French distinguish between at least five sizes of pea: (petits pois) moyens, mi-fins, fins, très fins, extra-fins, which Americanised Canadian French reduces to two: pois, and petits pois!

My chief memory of French gastronomy in my first year is of the pre-Christmas meal offered me by my landlord and landlady at the railway station restaurant. It would be absurd, comical even, to imagine taking someone out for a meal at a British station buffet, but French railway restaurants are an entirely different matter. We ate a most delicious meal, the highlight of which for me was the morels accompanying the tender steak.

In Besançon I earned my living by teaching adults spoken English using the then famous méthode de Besançon in six-week intensive courses. Especially after I married (at the end of the summer after my first year in Besançon), but even before, our students (Kay taught as well) took us out with them to explore the regional gastronomy. I had eaten well in Alençon, at Mont-St-Michel and in Paris, but was taken to another level on these occasions.

Our students came from all walks of life: mainly French or French-speaking from France or Africa, there were politicians, doctors, dentists, launderers, hoteliers, air stewards, civil servants, office workers, even a daughter who spoke French and German and wanted to know what her parents were saying to each other in English.

Without fail they took us out at the weekend. I discovered, and learned to appreciate and differentiate, the wines of the local regions of the Doubs, Jura and Côte d'Or, and further afield, as well as the dishes of these areas.

One of Kay's students in the summer of 1965 was the national minister of agriculture. Jacques Duhamel was also the mayor of the nearby town of Dôle. On 14 July he invited Kay, me and my parents. to spend the day with him in Dôle. At his apartment, wishing to offer us an apéritif, he asked me whether he should serve whisky or champagne. I thought the latter would be more acceptable. My father, inspired by the occasion, broke into song and gave a very acceptable rendering of La Marseillaise.

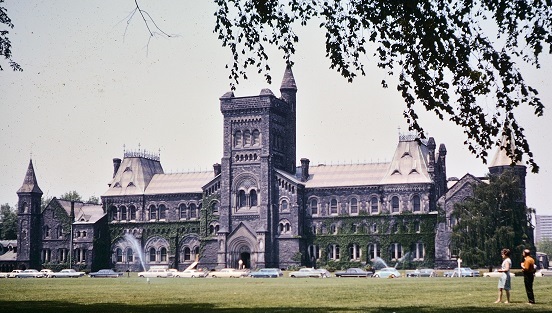

Then I emigrated to Canada. When I started my teaching career at the University of Toronto, the model for French was European (French) French. The switch to Canadian French was gradual, but well before I retired the norm was Quebec French. My first students were better at written French than at the spoken variety; by the time I finished, the reverse was true. I encountered three basic types of French: European French, Canadian (or Quebec) French, and immersion French. The majority of my students had learned the last, which contained anglicisms such as "Il/Elle est comme..." ("He's/She's like...") to introduce reported speech. They were incapable of using vous in addressing a single person, with the absurd, topsy-turvy result that I, a European, addressed them individually as vous, while they addressed me as tu!

The purse

Back in Manchester after my year in Alençon, Barrie and I had the good fortune of renting the flat in Moss Side that Bill and I had occupied in the last term of my first year. One evening, after a session of beer drinking, I noticed on a table, when we returned to the flat, a change purse which I didn't recognise. Greater still was my surprise to find Janine, come all the way from Alençon, asleep in my bed.She spent a few days in Manchester, including startling our French philosopy lecturer, Professor Sutcliffe, with her fluent reading of an extract from Pascal's Pensées.

I could only reward her persistent initiative by getting engaged to her. We had an engagement party at Christmas at her parents' in Liesle, in the Jura. Later on, my father and I picked up a crate containing her trousseau (or bottom drawer) at Hurn Airport in Hampshire. But then, as the date of the wedding approached, I got cold feet...

Fiançailles

The English language has fiancé and fiancée (or, indiscriminately, fiancee), so why not fiançailles, so much more expressive than the military-sounding engagement?I got engaged twice, first of all to Janine (see "The purse"). The wedding, when it took place, would be "sous les cloches" (literally "under the bells"), in other words, not in the main part of the church, but in the porch under the belfry. Since I was not a Catholic, there would be no nuptial mass. We didn't get married anyway. Looking back at it, it was not just my lack of readiness for the married state, it was also the threatening nature of the "bottom drawer", a relic of the days of the dowry.

Kay and I were to be married, without music or mass, in St Teresa's church in Wilmslow. Beforehand, I had to receive instruction from the priest, Father Mooney. Kay's mother treated Father Mooney with great deference. I should hasten to add that he was not the only person to receive her consideration; it was always easy to get into her good books with a box of chocolates - or a block of ice cream. The summer when I was Mr Softy (see "Holiday jobs"), I called in at the house in Wilmslow with a block of ice cream for her. The van had a motor to keep the ice cream refrigerated, so a neighbour knocked at the door to complain about the noise. Said Florence to her: "He's not an ordinary ice cream man, he's a graduate of Manchester University"!

The religious (Catholic) instruction (or indoctrination) was to be given in three one-hour sessions. At the first, Father Mooney and I, with our hands behind our backs, in the sacerdotal pose (not to be confused with "the missionary position"), walked up and down in the garden of the presbytery.

I was off to work as a guide at Mont-Saint-Michel (see "Holiday jobs"), so Father Mooney gave me a letter asking the curé there to give me the other two hours of instructiion. The curé at Mont-St-Michel was more interested in learning about Methodism, practically unknown in France, than in instructing me in the ways of the Catholic church, so we spent our time, to the accompaniment off a glass of calva, talking about John and Charles Wesley, and their view of the world.

Switzerland, the Alps and winter sports

|

The first time I went to Switzerland was with school-friend John Prior, in the summer of 1958. We hitched our way to Neuchâtel, the capital of the eponymous canton, where we stayed with a family whose son had stayed with John's family the previous summer. One day, John and I caught a train to Vue-des-Alpes in the Jura mountains, and climbed to the top to get our first glimpse of the Alps. I was later to return to Neuchâtel, in 1965, when I went there with wife Kay, her sister Carole and the latter's three-year-old Canadian-born daughter Kirsten. I remember Kirsten "seeing" her Poppy on top of several buildings in the town.

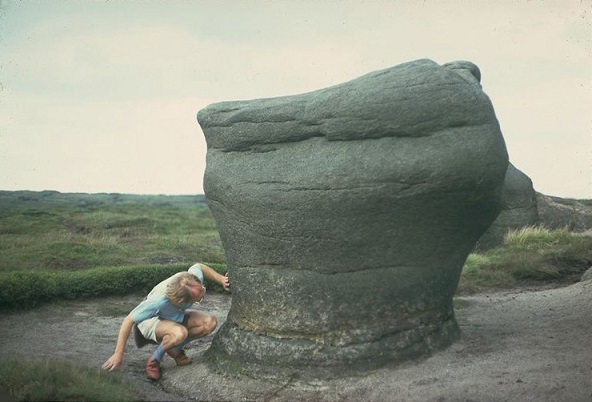

The second time I went to Switzerland was in 1960, after my second-year-summer-term-abroad in Montpellier. I celebrated my 21st birthday, at the time the age of majority, on the beach at Palavas-des-Flots (see "Early memories"), and went to Geneva to buy an Omega watch with the birthday money given me by my parents. Kay and I, usually accompanied by my parents or, especially, hers, went from Besançon into Switzerland several times, staying in hotels in Geneva, Bern, Interlaken, Lucerne or elsewhere mainly in the western part of the country. The road was often precipitous, and on one memorable occasion Kay's mother Florence, a champion back-seat driver, said urgently to her driver-husband: "Jim, you'll kill us all!" I have a vivid memory of a village high up in the mountains, where we bought a loaf of pumpernickel bread for our picnic lunch and where the only sounds were the humming of bees and the splashing of a mountain stream. Kay and I went particularly for the chocolate and made sure to fill the car with gasoline, then cheaper than in France. We went once to Sion, where we saw a spectacular son et lumière. On our way to and back from Sicily (see "Sicily"), Kay and I drove through the Mont Blanc tunnel. Kay and I were taken once by two of our students, in a floating Citroën DS, to a ski resort somewhere in the French Alps. Neither of us could stay on our feet skiing downhill. The only thing I mastered, more or less, was fish-boning up the (beginners') slope. One of my students, in my first year in Besançon, was a hotelier in the ski resort of Courchevel. I have seen the French Alps many times on television, as the Tour de France always includes several Alpine stages. During our time in Besançon, Kay and I bought a cowbell, typical of the mountainous country of the Doubs, the Jura and the Alps. We used it at home in Toronto to summon the children to the supper table. I heard cowbells often during my time in the East of France, but the most memorable occasion was in the summer of 2002, when my eldest daughter and I climbed the Col des Aravis, in the French Alps, where we had a wonderful open view and could hear, in the still air, the bells of cows grazing in the far distance (see left). |

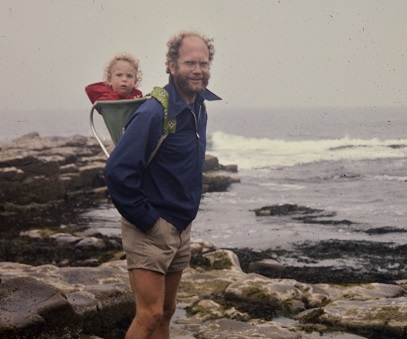

| When I emigrated to Canada, I, an Englishman, didn't know how to skate. During the first few winters, I tried, with the help of Canadian friends, but then gave up. After my experience in the French Alps, I didn't fancy downhill skiing, but I did get much enjoyment from two winter sports: tobogganing and cross-country skiing. My children and I got a thrill from tobogganing down the slope at Sherwood Park (see left and right), tumbling off when we go to the bottom, and several times skied at the Rosedale golf course. We skied once at the Metro Zoo, and were impressed when, topping a rise, we were confronted with a Siberian tiger. |

|

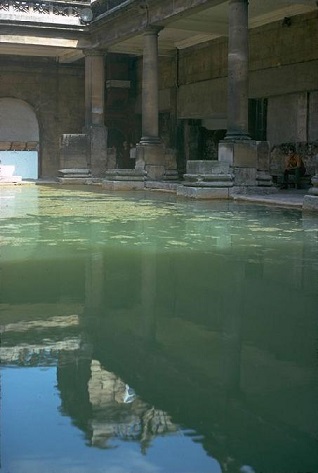

Sicily

Two others of Kay's students in the summer of 1965 (see "Vive la différence") were Francesca Vitale, the wife of a member of the Sicilian parliament, and her daughter. Francesca invited us to spend a holiday in Sicily. So, in September, we set off from Besançon in our little Renault 4, camping our way down through Italy to Reggio di Calabria and following the sun to save money, then crossing by ferry to Messina, thence driving to Palermo, our destination.

Two others of Kay's students in the summer of 1965 (see "Vive la différence") were Francesca Vitale, the wife of a member of the Sicilian parliament, and her daughter. Francesca invited us to spend a holiday in Sicily. So, in September, we set off from Besançon in our little Renault 4, camping our way down through Italy to Reggio di Calabria and following the sun to save money, then crossing by ferry to Messina, thence driving to Palermo, our destination.

After dinner at the Vitales', an experience to be repeated several times, we went to the apartment of Mme Vitale's mother, who spent the summer months at her second home in Enna. This was to be our home during our stay in Palermo.

We knew that Sicily was renowned for its Greek temples and Byzantine mosaics, so on our way down we visited the basilica of San Marco in Venice and the town of Ravenna (mosaics in both), and also the wonderful Greek temples at Paestum (see photograph).

We gazed at the magnificent mosaics in the Sicilian parliament church in Palermo and in the cathedral of Monreale. Typical of Byzantine Christianity are the representations of the Christ Pantocrator, a beautiful example of which we saw in the cathedral of Cefalù.

We also attended a perfomance at the Teatro dei Pupi in Palermo, visited the ruins of the Greek temples at Agrigento and the Roman mosaics of the Villa Romana del Casale at Piazza Armerina, and went up to the top of Mount Etna, but, for me, the highlight of our stay in Sicily was our visit, on a clear, sunny day, to the Greek temple and theatre at Segesta. Kay and I were the only visitors, and the loudest sound was that of bees collecting pollen. It was magical and timeless.

By contrast, when I returned to Sicily thirty years later for a conference of the Société de linguistique romane, the car park at Segesta was filled with coaches and cars. There was plenty of noise, the modern one of tourism.

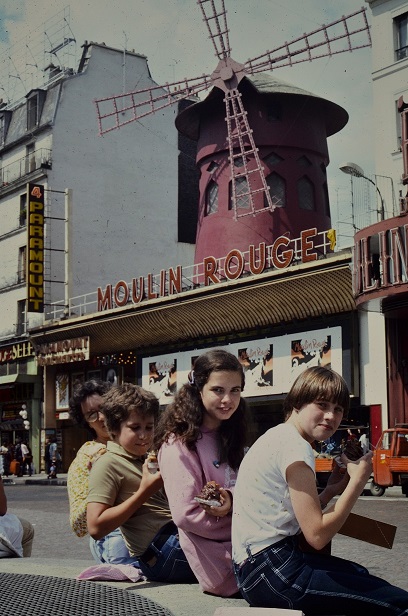

Paris

|

Paris, Paname, Lutèce. Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann, while keeping most of the old neighbourhoods, had the money to give the city its Vitruvian perspectives and Palladian beauty, sadly not available, after the 1666 Great Fire of London, to Charles II and Christopher Wren, who only managed to rebuild St Paul's. Paris is equally divided between the right-wing Rive droite and the left-wing Rive gauche, with the Ìle de la Cité playing referee in the middle. The right bank has the rich Rue de Rivoli, the swish 16e arrondissement, the old Halles and Bibliothèque nationale, the Centre Pompidou, the grands magasins such as les Nouvelles galeries (Galeries Lafayette) and Printemps (it used to have Marks & Spencer and la Samaritaine, among others), les Tuileries and the garden of the Palais royal, la Place de la Concorde and the Arc de Triomphe; the left bank has the Sorbonne, the Boulevard Saint-Michel, the publishing houses, the Eiffel Tower, le Bouvelard Saint-Germain, l'Assemblée nationale, le Jardin du Luxembourg; l'Île de la Cité has the Sainte chapelle and Notre-Dame. London, on the other hand has its power concentrated on the North Bank, with the City, Whitehall and Westminster (plus the Tower in times past); the South Bank, despite the panoramic views of the Greenwich of today and the magnificence of the Tudor past of Greenwich Palace, still retains the "forbidden" atmosphere of the bear pits and brothels of yore; there is nothing in the middle.

My first arrivals in Paris were at the Gare Saint-Lazare, the last at Charles de Gaulle Airport. I arrived by ferry, lorry (from the quayside to the railway station in Le Havre) and train from England; by scooter from Alençon; by coach (and ferry) from the West of England; by plane and train from England; by train from Besançon; by car from Nancy; by plane from Nice; by plane from Canada. Early experiences included: Ionesco's La Leçon and Les Chaises performed at le Théâtre de la Huchette, Claude Luter at le Caveau, rue de la Huchette; "French" onion soup at les Halles. Later: gazing each year nostalgically at the sculpture "le départ des Halles" in the church of Saint-Eustache. Amongst my favourite places and activities: the food section of le Bon marché; the Sunday street market in Rue Montorgueil; the local neighbourhood atmosphere of the Rue Mouffetard; the banks (quays) of the Seine, with their bouquinistes; the churches of Saint-Louis-en-l'Île, Saint-Séverin, la Sainte chapelle for concerts; the Arènes de Lutèce and the Jardin du Luxembourg for reading; Gibert on the Boul'Mich for books; the cinéma l'Épée de bois for films from all over the world; le Square (public garden) Théodore Monod to eat a tarte aux framboises bought at a nearby pâtisserie; cheap restaurants such as le Bouillon Chartier, le Tournbride, Chez Léon or le Polidor (used by Woody Allen in Midnight in Paris, one of my favourite films); any café to sit on the terrasse and watch the world go by as I sip a cup of café crème. I celebrated my successful thesis defence by taking Kay, my parents and Jean-Michel to dinner at la Godasse, no longer there hélas!, in Rue Monsieur le Prince, now filled with sushi restaurants. |

Besançon

I spent three years in Besançon after Manchester and before emigrating to Canada, studying structural linguistics and teaching English in six-week intensive courses (see "Vive..." and "Early memories").

I spent three years in Besançon after Manchester and before emigrating to Canada, studying structural linguistics and teaching English in six-week intensive courses (see "Vive..." and "Early memories").

The town itself is situated mainly in a loop of the river Doubs. The defence of the town was completed by the Citadelle, which closed off the town on the only side not bordered by water. It was said that the bullet holes in the outer walls of the citadel were the marks left by the shooting of collaborators after the Second World War.

The town was once part of the Spanish empire; a feature of its architecture is the Spanish balconies (often called Juliet balconies in English-speaking countries) to be seen on a number of its houses.

A speciality of Besançon is the griotte, a type of cherry. Griottes are steeped in kirsch and cherry juice, and sometimes coated with chocolate. One evening when I had badly cut my hand, Kay took me down to our landlady's flat. Madame Masson bound up my injured hand and made me partake of some of her griottes. She ran a haberdashery on the ground floor.

Life was fairly cheap. A packet of Gauloises and a coffee (espresso coffee in Engish), usually enjoyed on a café terrasse on the Place Granvelle, could be purchased for about two francs, more than we paid to eat a full meal, midday and evening, at the government-sponsored resto-U (university restaurant). University life in France was cheap; tuition fees were practically non-existent; the crunch for undergraduates came at the end of the preparatory year (propédeutique), when, at most, only half would go on to do a licence, the other half having failed the exams.

Kay and I attended mass (said in Latin) at the cathédrale Saint-Jean, a cavernous place with no redeeming aesthetic qualities. The music in most French churches is very poor. The hymns are feeble - France never had a Charles Wesley. There are nevertheless some very good choirs, but to hear great choral sacred music sung in its proper setting, one must cross the Channel to Anglicized England, to its cathedrals, Oxbridge college chapels, or the (Catholic) Brompton Oratory in London.

I returned to Besançon in June 1968, shortly after les événements de mai. The all-powerful secretary of the Faculté des lettres (faculty of arts) went by the name of Rouquérolles. Daubed on the walls of the Faculté was the slogan "couilles molles, Rouquérolles", a good rhyme expressing a very rude sentiment.

Nancy

|

Nancy has two dominant faces: that of the eighteenth century, when it was the capital of the Duchy of Lorraine, not yet part of the kingdom of France, ruled by the Polish Stanislav (or Stanislas); and that of the end of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth, when architecture and home decoration were dominated by the style of Art Nouveau, led by Émile Gallé, Louis Majorelle and the Daum family in the grouping known as the École de Nancy.

Duke Stanislas marked the centre of the city with two spaces. I attended the celebrations of the Feast of Saint Nicholas (6 December, whence Santa Claus) in the Place Stanislas, the main square of Nancy, and sang in a choral performance of Berlioz' Requiem mass in the neighbouring Place de la Carrière. I was doing research at the Institut national de la langue française and singing in the Chorale des Cordeliers. One year, I stayed in the flat of someone who had a friend who was a specialist of Art Nouveau glassware. From him I bought two small vases made and signed by Émile Gallé (see left). To get the official version of Jeanne d'Arc, one goes south to the village of Domrémy (her birthplace) and the nearby town of Vaucouleurs, where she went to seek permission to go to the court of Charles VII. To get the unofficial version, one goes north to the village of Jaulny, where Joan, another young woman supposedly having been burnt in her place in Rouen, is alleged to have married Robert des Armoises, borne his children and lived for a number of years in his castle.

|

Limoges

I was invited, in 1996 and 1997, by a French colleague to teach summer computer courses to Humanities students at the university of Limoges. The World Wide Web was in its infancy but already had many important sources for the study of human society and culture. In spite of the crude (by today's standards) state of the technology, I was able to screen for my students pertinent Web pages, prepared from my preparatory explorations. Of course, Google did not exist then, but there were several search engines to choose from. An added difficulty, particular to France, was the existence at that time of the country's own online network, Minitel.I was lodged in a pleasant flat to the south of the city in a building of flats on the banks of the river Briance. The banks of the Briance were an attractive place to have a picnic in the summer, and I invited Philippe, his wife and their two small children for drinks and games. The building was managed by the Benedicine abbey in the nearby town of Solignac, which was where I dropped off the keys. The abbey was founded in the seventh century, with most of its buildings constructed in the Romanesque style of the early Middle Ages.

The hamlet where I was lodged was called Pont Rompu, although the present-day bridge crossing the river was intact. My explorations of the region revealed that this was Richard Coeur de Lion (in English: Richard the Lionheart) country, the Limousin being under English rule in the twelfth century.

At the end of each day, I would stop off at a favourite pâtisserie to buy a tartelette aux fruits, often raspberries, which I would consume, along with a glass of chilled white wine, on the banks of the Briance.

Italy

|

I married Kay, who did a double honours B.A. in French and Italian at Manchester University. With her, and later, I went several times to Italy, to the point that I could gesture and speak quite fluently in Italian.

With two of the children we went several times from Nice to Sanremo (see left). With two or three of the children we went: to Pisa (daughter and I climbing the famous tower); to Florence, where we went to the Uffizi to see the Botticellis and other paintings, admired, in the Piazza della Signora, the statues of David by Michelangelo and Perseus by Cellini, and gazed at the beautiful doors of the Duomo baptistery; to Siena and its immense Piazza del Campo; to the towers of San Gimignano; to the watery city of Venice (see "Curiosity"). I went several times to Venice, including, as a student, a visit to one of the islands of Murano, where I bought a typical vase, which I still have. Early in our marriage, Kay and I went to Sicily (see "Sicily"), stopping on the way back in Rome (we drove past the Colosseum, and went on foot to visit St Peter's - it was the time of Vatican II, and we saw the cardinals descending the steps as they left the huge church) to see the subject of Kay's M.A. and Ph.D. theses, the poet Giuseppe Ungaretti. He took us, and his Czech translator, to dinner in a Tuscan restaurant, where I had the most delicious steak I have ever eaten. While he talked about himself in the third person, he, a man in his late seventies, ogled the young waitresses. On the way down to Sicily, after visiting Venice and Ravenna, we spent one night at the campsite of Fiesole, above Florence, which we visited the following day. Since we had little money and were thus rising and setting with the sun, it was still almost dark when we went to early mass in Fiesole. I was struck by two things, typical of a Mediterranean country: apart from the priest, I was the only man present; Kay and I were the only two not in black (the congregation comprised about six elderly women, plus Kay and me). Further south we visited the wonderful Greek temples of Paestum, finishing our visit with a refreshing citron pressé. In Calabria, at the toe of Italy, we entered a village shop in search of lemons; the conversation within immediately stopped, although we wouldn't have been able to understand a word of the local dialect. On another visit to Italy, this time with the children, we stayed with Kay's former Manchester prof, Kate Speight, in her converted watchtower high up in the hills of Tuscany. Once with Kay and once with two of the children as well, we went to Lago di Como and Lago di Garda, two beautiful lakes. |

Ireland

I have been to Ireland three times. The first was in the company of my parents and my brother, when I was recovering from the breaking-off of my engagement (see "The purse"). We went to Ulster, where we stayed with an extremist Protestant family (no piano-playing of Mozart on Sunday, only hymns!). Driving to Derry and Donegal, we came upon a living Irish joke (an Irish joke in England is the equivalent of a Newfie joke in Canada, or an histoire belge in France; an Irish joke told by an Irishman or woman is about Irish people). We could see, in the distance and coming towards us, a car straddling the painted centre line, presumably taking it for a guide. Fortunately, the driver had the sense to move to the left before passing us.

I have been to Ireland three times. The first was in the company of my parents and my brother, when I was recovering from the breaking-off of my engagement (see "The purse"). We went to Ulster, where we stayed with an extremist Protestant family (no piano-playing of Mozart on Sunday, only hymns!). Driving to Derry and Donegal, we came upon a living Irish joke (an Irish joke in England is the equivalent of a Newfie joke in Canada, or an histoire belge in France; an Irish joke told by an Irishman or woman is about Irish people). We could see, in the distance and coming towards us, a car straddling the painted centre line, presumably taking it for a guide. Fortunately, the driver had the sense to move to the left before passing us.

The second visit was our honeymoon, which Kay and I spent in a cottage in Connemara (see left). One day, we decided to go to the nearest town, Clifden, nine miles away. We didn't have a car, but we were told we would be picked up by the first car going our way. We had walked eight miles before the first car came along...

The third time I went to Ireland was when Kay and I decided to celebrate 50 years of marriage and divorce by renting a cottage in Dunmore East, near Waterford. The lady who ran the bakery told us wearily that a Canadian had come up to her in California and said "Thank goodness there's someone else here from a Commonwealth country". We, equally Canadian, certainly didn't make the same mistake. The driver of the bus driving us from the car rental office to the airport terminal told us an Irish saying: "Take your time, but hurry up".

Wild Wales

My brother moved from England to West Wales, first of all living in a caravan, then in a cottage called "Pen Rhiw" (literally "top of the hill"). When he lived in a caravan he washed himself and his clothes summer and winter in the cold, pure water of the nearby stream. The water supply to his cottage came off the hill and was tested purer than the mains supply in the village.

My brother moved from England to West Wales, first of all living in a caravan, then in a cottage called "Pen Rhiw" (literally "top of the hill"). When he lived in a caravan he washed himself and his clothes summer and winter in the cold, pure water of the nearby stream. The water supply to his cottage came off the hill and was tested purer than the mains supply in the village.

We went to a pub one evening and participated in the Welsh tradition of the lock-in, leaving the pub by the front door at closing time, and going back in by the back door to continue our drinking. Another evening, we went to a pub called "The Last Dog on Earth", where we encountered a complete mix of ages (incuding children), classes and races. It was the most democratic pub I have ever been to.

A typical evening at the cottage involved smoking up in front of the coal fire, drinking home brew and listening to Tangerine Dream or Mike Oldfield while watching the images of the television set with the sound off, trying to give sound + image some semblance of meaning. The world conjured up by the grass-affected mind can be quite wonderful. Nigel grew his cannabis in his own garden.

Wales has no motorways (except in the Anglicised south), with the result that life tends to go on unhindered by authority. The water at the cottage was heated by an Aga cooker; the food was cooked on an electric cooker, which had a grill for toast and mackerel - the fish van came to the village on Wednesdays. I was often there in late summer, and picked mushrooms in the fields and blackberries in the hedgerows for my breakfast. Life was somewhat like Cider With Rosie, but in late 20th-century Wales, not early 20th-century Gloucestershire.

Nearby are the ruins of the abbey of Strata Florida, those of a Roman settlement on the banks of the River Brefi, the dramatic cliffs near Cwm Tydu (see left), a path along what was the embankment of a railway line from Lampeter to Aberystwyth, and, in Lampeter, St. David's College, the first university in Wales and only two years younger than the University of London. Many English students who come to St. David's stay on in Celtic Wales, which they find saner than Anglo-Saxon England.

Nearby are the ruins of the abbey of Strata Florida, those of a Roman settlement on the banks of the River Brefi, the dramatic cliffs near Cwm Tydu (see left), a path along what was the embankment of a railway line from Lampeter to Aberystwyth, and, in Lampeter, St. David's College, the first university in Wales and only two years younger than the University of London. Many English students who come to St. David's stay on in Celtic Wales, which they find saner than Anglo-Saxon England.

One of the activities which Nigel and I shared was attending festivals: Dance Camp in Pembrokeshire, a Harvest Festival in Fishguard, the Glastonbury Festival (three times), an Earth-Mind-Body Festival in Sussex. Nigel was usually involved in selling (one of his friends, 'Cosmic' Pete, made candles, incense and essential oils), so at Glastonbury we were away from the mud in the Healing Field. I wasn't particularly attracted to the airy-fairyness of New Age, but I did enjoy the near-anarchy and sheer inventiveness to be found at most festivals. One of Nigel's friends said to me one day that I was what sounded like "a Middle Age dippy"; I realised he was calling me a "middle-aged hippie".

The beginning of my favourite way back from Nigel's was via twisty, narrow lanes, with the car brushing up against the hedge on either side, a hedgehog crossing, a Roman road, Merlin's Seat (amongst the earliest accounts of the Arthurian legends are the stories contained in the Welsh-language The Mabinogion) and a ford, coming out on the A482 near Ffarmers and Pumsaint.

Holiday jobs

I had a number of jobs during the Christmas and Summer holidays between the ages of about 12 and 25. This besides being a paperboy during term-time.The first was accompanying Uncle Cale in a little van when he delivered groceries from the International Stores in Hythe to customers living in Beaulieu, Blackfield or Dibden Purlieu. Then I helped him in a larger van on his greengrocer's round in Marchwood and Dibden. I learned to "see" and "feel" a pound of potatoes of apples.

In the subsequent summers I weeded 1000 Christmas trees for Uncle Freddie at a farthing a tree, and helped his nephew feed and clean out the pigs. That was on the Furzewood Estate at Butts Ash.

That was the last job obtained through nepotism. When I was 17, I worked at the UnaStar Laundry up Winchester Road. There were the regular women and several of us schoolboys. We entertained one other. The women taught us dirty songs, and we thought up "Luddite" ways to amuse them. Of the former, I remember the "Caviar comes from the virgin sturgeon" song. One instance of the latter: sending a jelly baby between two sheets through the ironing press; when the sheets came out at the other end, they had the shape of a giant jelly baby imprinted on them.

My last summer job in Southampton was at the smelly Calor Gas factory at Millbrook. The job consisted of filling canisters with gas and loading them onto delivery lorries. A number of the lads amused themselves by spraying each other with gas by chasing one another holding a canister and opening the nozzle.

A pre-Christmas job I had for a number of years was working at the post office, delivering letters, delivering parcels, sorting letters or sorting parcels. I did them all. One year, I worked at the foreign parcels office at Redbridge. On Christmas Eve we had one delivery to sort at 6 p.m. then the last one at 10. In between, we all went to the pub, where I had several rum-and-blackcurrants. Feeling completely sober, I rode home on my bike, thinking it wise to chew a bit of spearmint gum before reaching home. My mother was not deceived however, and so I did not enjoy the subsequent Christmas Day.

After Christmas, I worked several times in the January sales at the department store Edwin Jones. The first time, I was in the rubbish department; one day, I slipped on wet ash in the yard, fell, cut my hand and had an anti-tetanus shot. That was when I discovered I was allergic to penicillin, suffering painful after-effects. The other two years I worked as a shop assistant inside.

After Christmas, I worked several times in the January sales at the department store Edwin Jones. The first time, I was in the rubbish department; one day, I slipped on wet ash in the yard, fell, cut my hand and had an anti-tetanus shot. That was when I discovered I was allergic to penicillin, suffering painful after-effects. The other two years I worked as a shop assistant inside.

In my student years I found casual jobs in Manchester. After working as an insurance collector during term-time in Moss Side, I worked for a week the first summer as a vacuum cleaner salesman. During that week, the company changed addresses, and the one sale I managed to make using a very misleading patter and demonstration earned me a bonus, my team leader a bonus, and the head salesman a bonus. Something was very wrong, so I left. I then worked very peacefully for a soft drinks company, Jewsbury and Brown, spending most of my time checking invoices at the office, and selling soft drinks at a cricket test match at Old Trafford. Since the invoice-checking didn't take me long to complete, I spent a lot of time typing out poems addressed to my girlfriend Gwen.

In subsequent summers in Manchester, I worked once at the Colgate factory in Trafford Park, and once as Mister Softy, driving a van and selling ice cream. Working the night shift at the Colgate factory, the normal job for the three of us casual students was to clean the factory floor. It took us about two hours of concentrated work to do this, so we spent the rest of the time sleeping or reading (I managed to read all of Proust while there). On our last week (last because we left), however, we were put on the assembly line. The sheer monotony of this led to several results, some inevitable, some unexpected, including: for diversion (cf. UnaStar), putting a dead mouse in a container of Colgate cleaner; passing everything as correct (mainly weight of filled cartons); Pete, a medical student who worked as an intern during the day, thought the date stamp was: a) his girlfriend's change purse, b) a bar of chocolate. The three of us decided it was time to move on.

My two best summer jobs, however, were neither in Southampton, nor in Manchester. After my second year at university, I stayed with the family of flat-mate Barrie and worked, like him, as a conductor on the Southdown buses based in Bognor Regis. Those were the days of double-deckers (single deckers were rare and known as "one-man bandits"). Standing on the open platform at the back of the bus, the conductor could look up the skirts of young girls going up the stairs; while collecting fares, he could look down their blouses! I got my comeuppance, however (see "The fall"). Since many regular conductors took their holidays during the summer, I was often asked to do two shifts a day, thus earning a lot of money. I liked the challenge of a full bus, the sleep-time of an empty bus, but not the boredom of a half-full/half-empty bus. I repeated the experience in the September before my final year.

My two best summer jobs, however, were neither in Southampton, nor in Manchester. After my second year at university, I stayed with the family of flat-mate Barrie and worked, like him, as a conductor on the Southdown buses based in Bognor Regis. Those were the days of double-deckers (single deckers were rare and known as "one-man bandits"). Standing on the open platform at the back of the bus, the conductor could look up the skirts of young girls going up the stairs; while collecting fares, he could look down their blouses! I got my comeuppance, however (see "The fall"). Since many regular conductors took their holidays during the summer, I was often asked to do two shifts a day, thus earning a lot of money. I liked the challenge of a full bus, the sleep-time of an empty bus, but not the boredom of a half-full/half-empty bus. I repeated the experience in the September before my final year.

After my year in Alençon (see "Vive...") and again before I got married, I worked as a guide at the abbey of Mont-Saint-Michel (ditto and see pics), earning a lot of money through the keeping of two thirds of the tips I received (the other third went to the regular guides). I liked to have an interested (thus interesting) group of visitors. If they were uninteresting, I tended to switch to automatic pilot, inevitably wondering at some point what I had already told them, an unnerving experience. One visitor made the priceless remark that the monks must have had a hard time keeping the sand in the bay flat; another wondered how Tombelaine (a large rock out in the bay) stayed in place when the tide came in.

The fall

I had a fall one day, when I was a student. It was in Bognor Regis, on the Sussex coast, where I was working as a bus conductor during the summer holidays. I was standing on the open platform at the back of the bus in the conductor pose, left hand in my pocket, right hand nonchalantly holding onto the bar, watching the world go by. The bus was going slowly through the centre of town. Suddenly I saw a girl I knew standing on the pavement. She smiled at me and waved to me. I smiled at her and gave her a wave with my right hand. Just then the bus accelerated, and I found myself on my bum in the roadway with coins spilling out of my bag all around me. Too embarrassed to look at the girl, I started to pick up the money, helped by a Good Samaritan who came to my aid. A few minutes later the bus driver came running up, his face as white as a sheet. By the time the story of what had happened had passed from mouth to mouth from the back of the bus to the front, he had visions of my needing a stretcher to the mortuary. One of the other bus drivers had a reputation as a story-teller. And so several days later, when I was at the bus depot in nearby Chichester, an inspector came up to me to ask if I was the conductor who had seen his girlfriend with another man and jumped off the bus to go after him...

A cappella

Maddy Prior sings a song called "Acapella Stella" written by her husband Rick Kemp, both of Steeleye Span fame, but this is about Renaissance polyphony.A member of St. Michael's Cathedral all-male choir, I long thought that, as in the sixteenth century, the soprano line was always sung by boy trebles, the contralto notes by boy altos. This in the modern world, according to my way of thinking, was due to the inevitable vibrato of women's voices.

This misconception, based on the enduring influence of nineteenth-century opera singing, was shattered at a concert of polyphonic motets sung by the Bevan Family at Downside Abbey, five young sisters and five young brothers, all in their twenties or thirties, their voices trained by their mother and conducted by their father. The singing was superb, with not a trace of vibrato.

I have since had the privilege of talking to Maurice Bevan, one of the ten, after a concert given by the Deller Consort, of which he was a member, and of seeing Emma Kirkby sing at the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. One of the best recordings of Allegri's Miserere is that by the choir of Clare College, with its high C sung by a young woman.

Grass rubbing

On sabbatical in East Anglia, in the days when one could get at the originals, I explored the region by way of the rubbing of monumental brasses.

On sabbatical in East Anglia, in the days when one could get at the originals, I explored the region by way of the rubbing of monumental brasses.

Using my detailed Ordnance Survey maps, I would choose an area, determine from my collection of books on the subject which churches held which brasses, then, with itinerary and list, set off in my car to find out who to get the church key from and who to pay. Inside the church I would examine the brass and take its measurements.

On a second trip I would make the rubbing. The supplies - paper and wax crayons - I would buy in an art supplies shop in Cambridge. I ended up doing rubbings in Essex, Suffolk, Norfolk, Cambridgeshire, Northamptonshre, Kent and Surrey.

In this way, I discovered little villages well off the beaten track. I particularly remember the village of Westley Waterless, in Cambridgeshire. When I arrived, in the morning of a mild winter day, there was no sound, nobody in sight. The village pond was surrounded by daffodils and had ducks swimming on it. Another memory is of the carpet of snowdrops in the graveyard of the church in Felbrigg, Norfolk.

The rubbings were hung, sometimes several on top of one another, on the walls of the rented house in Stratford St. Mary, and, at the end of the year, as part of a fête, in the cloisters of the Franciscan Friary in West Bergholt. (It was at the friary that I learned one of the popular etymologies of the English fish and chip shop, set up, in the Middle Ages, by a chip monk and a fish friar.)

I am the proud possessor of over fifty rubbings, including those of famed brasses such as those of Henry Bures at Acton, Sir John de Creke and wife Alyne Clopton at Westley Waterless, Margaret Peyton at Isleham, and Sir John and Lady Ellen de Wautone at Wimbish.

On many of these outings I took my two-year-old son. We were going "grass rubbing", a great adventure. While I started on a rubbing - carefully cleaning the brass and covering it with masking-taped brass-rubbing paper before starting in with the crayon - little son, armed with paper and drawing crayon, would start on his "grass rubbing" (before then, while I was writing my doctoral thesis, he would sit on my study floor with paper and crayon, writing his "feesis"). Before finishing my rubbing, we would have our picnic lunch, either on the grass or in the car, after which I settled him down for his nap on the back seat.

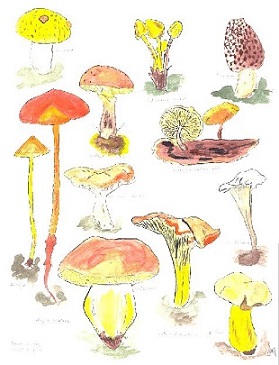

Edible fungus

For my second sabbatical, I decided that my centre of interest for explorng the region around Bath would be mycology. One of the interesting things about this subject is that there is no universally accepted terminology for the different species and genera of mushrooms, the classification and nomenclature of fungi differing from book to book, and language to language. Latin and vernacular names vary from one to another.

For my second sabbatical, I decided that my centre of interest for explorng the region around Bath would be mycology. One of the interesting things about this subject is that there is no universally accepted terminology for the different species and genera of mushrooms, the classification and nomenclature of fungi differing from book to book, and language to language. Latin and vernacular names vary from one to another.

I had always been interested in mushrooms. When I was quite small, my mother would send me out in the early autumn morning to scour the nearby fields for field mushrooms and horse mushrooms, which she would then fry as part of our breakfast. I learned early on the thrill of seeing white caps peeking above the green of the surrounding grass.

Among my experiences during the year in Bath and since: finding edible boleti in the woods near my brother's house in Ceredigion; finding, with my brother, "magic mushrooms", which we then consumed in magic mushroom tea, causing me to see brilliant stained-glass windows when I went to bed; finding, and eating fried or in soups, giant puffballs in Hampshire and Killbear Provincial Park; finding delicious chanterelles in the woods of Killbear Park.

At dance camp near Milford Haven, in Pembrokeshire, I attended a workshop on rooting. The workshop leader asked the participants for suggestions for the mantra which we would chant while stamping around getting rooted. My suggestion - "edible fungus" - was adopted by the group.

Tintin

My third sabbatical was spent in Nice. My younger daughter was put in the final year, class CM2, of the local primary school. During the first term, her teacher kindly did not assign marks to her work while she learned (European) French. By the time the second term started, she was completely fluent, so her teacher treated her like everybody else.In the French school system many schools are closed on Wednesdays, with classes on Saturday morning. So Wednesdays were Sarah's and my special day for exploring. Our travels, sometimes including Sarah's Canadian friend, included taking us to: le Mont Chauve, with its World War 2 barracks; the abandoned hill town of Neuchâtel; Roquebrune-Cap-Martin; le Trophée des Alpes.

My daughter shared my passion for books. It was during this year that I gave up reading to her at bedtime, halfway through David Copperfield. But we shared another book project.

We spent several Wednesdays building up a complete collection of second-hand Tintin albums, scouring the bookshops of Nice. When our collection was complete we were very proud of our achievement.

Woman's Hour

In the early 1980s, I had the task of proofreading the 672 double-column folio pages of the keyboarded early French dictionary Thresor de la langue françoyse of Jean Nicot, better known for the introduction, while king's ambassador to Portugal, of the tobacco plant into France and the words nicotine and nicotiana (known at the time as l'herbe à Nicot). During his retirement in le Bois-Robert, he took an existing French-Latin dictionary and added commentaries, in French, on many of the French entries.

The text had been captured, partly by a keyboardist at the Institut de la langue française in Nancy and partly by a research assistant at the University of Toronto. The two, technically quite different, were merged by a programmer at the Computer Service (only one at the time) at the University, and I did my proofreading from a printout.

For two summers we exchanged houses with an English academic from the Universiity of Exeter. While my forbearing wife took our children canoeing in Exmouth or bathing at Sandy Bay (I occasionally went with them), I tackled the immensely boring job of reading the capture of Nicot's Thresor, comparing it to a facsimile reprint edition of the original. The biggest obstacle was the tendency to "make sense" of the forms in front of my eyes, to confuse one word with another (think of discrete and discreet in English).

Fortunately for my sanity and for the accuracy of my reading, I hit upon the idea of occupying my thinking mind with something else. I had a radio, and so spent many an hour listening to the fascinating reports, interviews, debates - on health, education, cultural and political topics - and dramatisations of the programme Woman's Hour, while my eyes did the proofreading. The odd combination worked well.

Devon

So enamoured were we with Devon that the following summer we rented, for a week each, a house in Zeal Monachorum, a cottage in Moretonhampstead and a caravan in Sandy Bay.

Kay's sister, brother-in-law and their four children also spent a week each summer in their caravan at Sandy Bay. We did things together with them, including exploring, along with my widowed mother, the beauty of Dartmoor (we had been to Exmoor, in North Devon, during a previous summer spent in Ditcheat, in Somerset).

Bluebells

I have various memories of bluebells (in Canada, the equivalent are called scilla). The first was when I was a little boy on a visit to see Auntie Blake and Dorothy. The woods at Ashley were full of bluebells covering the ground amongst the trees.

Then, when on sabbatical in Stratford St. Mary, I remember going for a walk in the nearby woods in the Stour valley and coming upon the dreamlike scene of a carpet of bluebells, with, standing in their midst, a white peacock (escaped from a nearby stately garden). The scene had the mystical quality of the unicorn garden in the New York Cloisters' tapestry, but in three dimensions and true colour.

The third memory is of a stop at the beginning of the Cambrian Pass on our way to visit my brother in Llanddewi Brefi. We stopped because my mother suffered from migraines. I took several photographs of the moss-covered tree branches and the bluebells growing among the trees (see left).

Bluebell carpets are both magical and the harbinger of warm weather.

The train

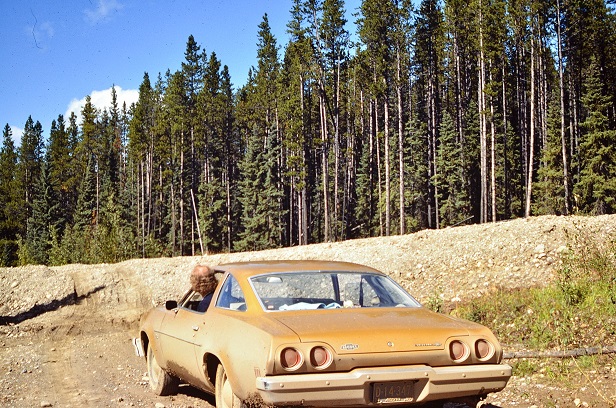

In 1974, my parents, Kay, our two children and I spent two and a half days in a CP train, travelling from Toronto to Vancouver via Calgary and Banff. We experienced none of the high jinks of Some Like It Hot or Laurel & Hardy's Berth Marks, nor the drama of Murder on the Orient Express or Le train, but we did enjoy seeing the vastness of Southern Canada and took pleasure in the food served on a crisp white linen table cloth with silver cutlery and linen napkins.

We left in the late afternoon of Day 1, and spent the whole of Day 2 going along the North shore of Lake Superior. After lengthy stops at Winnipeg in the evening of Day 2 and Medicine Hat and Banff on Day 3 (there were others), we entered the Rockies, where we were told to go to the observation car, either at the front or the back, to see the other end of the train higher up or lower down entering or leaving the mountainside. On Day 4, we descended the Fraser Valley and arrived at our destination.

I got up early each morning so that I wouldn't miss anything, and particularly enjoyed the gorgeous sunrises and sunsets.

St Petersburg

For several years I had wanted to go to Leningrad, to visit The Hermitage and see the magnificent churches dating from the time when Catherine the Great invited Voltaire and Diderot to her country.

For several years I had wanted to go to Leningrad, to visit The Hermitage and see the magnificent churches dating from the time when Catherine the Great invited Voltaire and Diderot to her country.

Then, when Leningrad had become St Petersburg again, I received an invitation to give a paper at a conference in Tampere, in Finland. Aha!

We drove from Molshem, in Alsace, through Germany, Denmark and Sweden, leaving the car in the parking lot of a hotel in Porvoo, in Finland. From there, we travelled by train to St Petersburg.

At the Finland Station, we were accosted, in English, by a young man, who became an imporant part of our stay in Russia. He said it would be cheaper to get to the hotel if we caught a taxi a hundred yards away rather than in the station forecourt. That proved to be the case (the same applied to taking a taxi from the hotel). In exchange for supplying him and his girl-friend with hot dogs and beer at the hotel bar, he found for me a source of American dollars and supplied me with other money-saving tips.

We found that shops and cafés accepted either dollars or roubles, never both. Our stomachs would have to wait until we got back to Finland, but nevertheless I enjoyed the coffee with Bailey's Irish Cream in place of milk served at the hotel bar (paid for in dollars), and we both appreciated the caviar consumed in a café on the Nevsky Prospekt (roubles).

The feast for eyes and ears included: a visit to the collections of The Hermitage; the skyline of St Petersburg; a visit to the Summer Palace, where we found a Mozartian chamber quintet in period costume playing in the gardens; an evening of wonderful dancing, ballet, choral singing and instrumental music given by a St Petersburg company in the magnificent concert hall of the hotel; walking around the city and seeing people playing chess everywhere.

On the ferry returning from Helsinki to Stockholm we passed by little islands which beat anything I had seen in the Saint Laurent.

Denmark

|

I had a cousin, daughter of my mother's sister, who had married a Dane and lived near Copenhagen, in Brøndby, I think. In 1968, Kay and I rented a Peugeot 404 station wagon in Besançon, and drove, with our baby daughter in the back, to pick up my parents, who had flown over from England, at the Porte d'Italie, in the southern outskirts of Paris.

On the way, we spent a night in Liège. Then, in Amsterdam, we took a canal boat ride, where our daughter had her first taste of Fanta (see left). We spent the night in Groningen, where Louis, a friend from my Besançon days, lived with his family. His father was a butcher, so we tasted his sausage at dinner. Then on to Lübeck, where we caught the ferry to Denmark. Wendy and Per, their two boys and two girls, plus Per's widowed father, made the five of us welcome. I remember the trips: to the beach (somewhere north of Copenhagen), with its glorious cliff-top dog roses and invigorating sea; to the Viking museum in Roskilde; an evening at Tivoli; a shopping trip to Copenhagen. There were bicycles everywhere. We left impressed by a beautiful, civilised country (one of my favourite novels is Rose Tremain's Music and Silence). We never made it to Jutland, the land of my New Forest forebears and the setting of one of my favourite films, Babettes Gæstebud. On the way back, we stopped in Groningen to pick up Louis and his sister, who accompanied us to Amsterdam (they travelled in a separate car). We got the address of a hotel from the chamber of commerce, and I bravely followed Louis (who had my father in his car) over bridges and alongside canals, all the time fearing I would never see my father again, as Louis was the only one of us who had the address of the hotel. And so back to France. After a restaurant meal of game hens and wild strawberries, my parents caught a plane back to England from Le Bourget airport. Kay, our daughter and I continued on back to Besançon. |

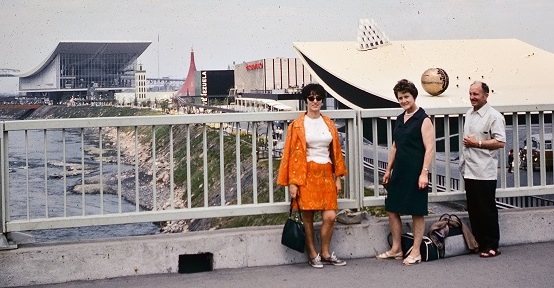

Spanish culture

In 1958, John Prior and I visited the Brussels World's Fair. Turning a corner in the Spanish pavilion, we were almost bowled over by Salvador Dali's painting Cristo de San Juan de la Cruz (Christ of Saint John of the Cross).In 1989, Yvette and I went to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostella, the destination of the Camino de Santiago. I had read Cuelho's Pilgrimage, which prepared me for our stay in Santiago.