Collecting

|

Rice pudding < adapted from Mum's recipe Grease oven-proof dish Put 2 heaped tablespoons of round rice in dish Add 2 cups milk Add 1 cup hot water from kettle Pinch of salt 2 tbsp honey Knobs of butter Sprinkle pinch of nutmeg

Preheat oven to 300F. Put dish in oven and lower |

As a boy, I collected stamps, eggs, cheese labels and matchbox tops. As a student, I collected beer mats. In middle age, I made a note of aeroplane flights I had taken. During sabbatical leaves, I made and collected brass rubbings (see "Grass rubbings"), sought edible fungi (see "Edible fungus"), and hunted down, with my younger daughter, second-hand copies of Tintin albums, ending up with a complete collecton. In retirement, a keen amateur cook and baker, I collect recipes (see left).

Times and technologies change. In some countries, human-sold stamps have been replaced by machine-produced labels. Zoological and botanical specimens are no longer gathered for collections or as a means of identification, replaced in the latter role by image-recording. A taste for processed cheese was replaced in me by one for the (unlabelled) real thing. Matchboxes have been replaced by matchbooks, petrol, gas and, now, digital lighters. Beer mats are vehicles for advertising, and so have survived. Stamp-collecting and coin-collecting are dignified with the technical names philately and numismatics respectively. Other types of collecting are often denigrated: people collecting train numbers, usually called train-spotters, are referred to as "anoraks"; those collecting sightings of bird species are called "twitchers" (cf. "uniforms" and "suits"). Charles Darwin was not a twitcher but rather a respected ornithologist. |

Flights of fancy and X marks the spot

I remember two secret tunnels from my childhood. One was an underground passage allegedly built during the Second World War to allow employees to escape from the Maybush Ordnance Survey headquarters into a field at the bottom of the road where I lived; the field exit was filled with bricks when we boys tried to explore it in the late 1940s, so we were unable to prove or disprove the story. The other tunnel was much older, allegedly leading from Roche Abbey to the Crags above Maltby in the West Riding of Yorkshire; my father told me he had explored it when he was a boy, but when I saw it, it was completely blocked up.During the war my father was in the RAF stationed a long way away. One night, when my mother and I were down in the bomb shelter in the garden, she asked me what I wished for most. I said "Daddy", and just then Daddy came down the steps into the shelter! I have wondered since if that memory is a telescoped one, or if my wish was what Mummy was hoping it would be. But it remains a magical memory.

Real or imagined places are the themes of Gabrielle Roy's novel La Route d'Altamont and of Françoise Hardy's song San Salvador (song written by Hughes de Courson). Roy wonders whether a road she took with her mother really exists (she is unable to find it again); Hardy wonders "Qui sait si ce pays a jamais existé".

Bridges

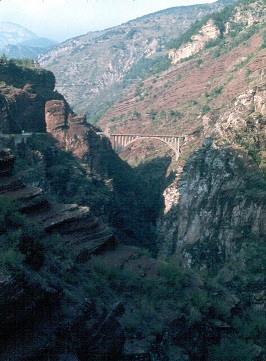

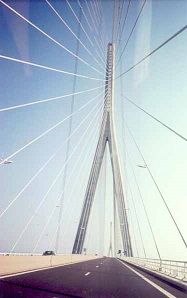

(Hover with cursor over image to see title, click to enlarge in second window.)Bridges represent fascinating concepts since they link here and there. Physical bridges are constructed to allow people, livestock, horses, carriages, carts, cars, other vehicles, trains or water to go from A to B, which are locations higher than the valley, generally containing a waterway (most often a river), spanned by the bridge. The higher A and B are above the bottom to the valley, the more spectacular the bridge - such as the one seen in the Var Valley in the South of France (see photo 1).

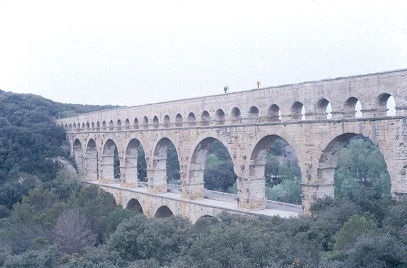

The Romans famously built many aqueducts and viaducts, such as the Pont du Gard in the South of France (see photo 2).

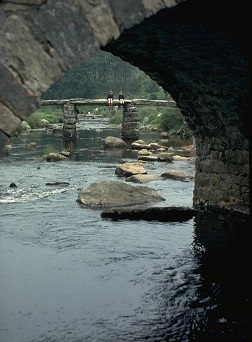

In the Middle Ages and later, many towns and villages had packhorse bridges, such as the one at Bruton in Somerset (see photo 3). Equally old, if not older, are the clapper bridges typically to be found on Dartmoor (see photo 4).

A bridge can be a humble one, made of wood, giving access to a private dwelling, such as the one seen in Connemara (see photo 5), or a grandiose one linking two countries, such as the Peace Bridge near Niagara Falls (see photo 6).

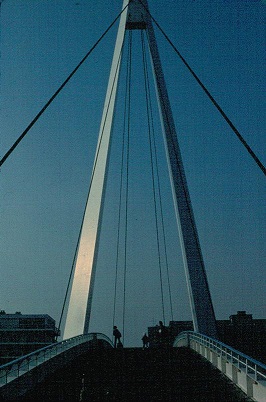

The more advanced the technology, the longer the span between A and B can be. Such is the case of the various bridges crossing the River Avon and the Severn Estuary in the West of Great Britain (see the small bridge crossing the River Avon in photo 7), or that joining the Isle of Skye to the mainland, or the one linking Denmark to Sweden, or the various modern bridges spanning the River Seine (see photos 8, 9, 10).

The bridges of London and Paris are celebrated in various songs and accounts. More intimate are those to be found in modest Pont-L'Évèque (photo 11), Cambridge (photo 12) or a village in Alsace (photo 13).

In Alberta I saw an old trestle bridge, built of wood to carry trains (see photo 14).

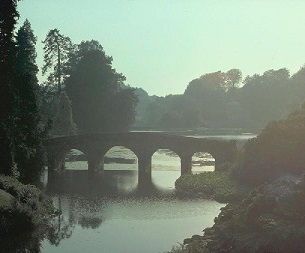

Lastly, there is the purely decorative or non-functional bridge, such as the Palladian Bridge designed in the eighteenth century by Henry Hoare as a garden feature at Stourhead in Wiltshire (see photo 15).

Salutes

|

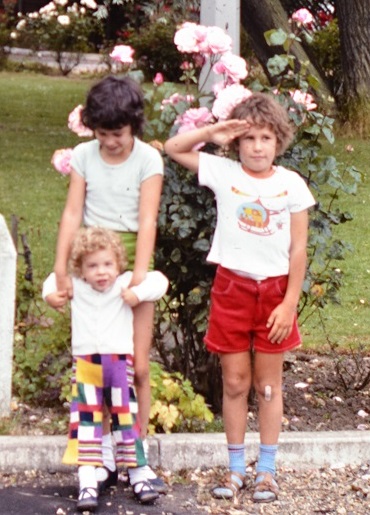

Both my son and my brother are saluting in these photographs. Why? In English, a salute is normally restricted to the military or para-military (Boy Scouts, Wolf Cubs, etc.) spheres. The word comes from the Latin salutare via Norman French, where the meaning is more general, signifying a sign of recognition and respect towards an acquaintance, as in the Latin salve or the French salut. The opposite to a sign of respect would be the North-American finger, the British two fingers or the French bras d'honneur.

Distant signs of recognition and respect include the generalised and cross-cultural wave. Verbal salutations in English include hi, hello, hey, ahoy, good morning, g'day, wotcher, what ho. Physical greetings include the handshake, the high five, the cheek kiss, the hug, the Inuit kunik and the Maori hongi. In Anglo-Saxon culture, the handshake is generally reserved for introductions or agreements, the high five is a modern sign of shared triumph, the cheek kiss is often referred to as an "air kiss" (no physical contact), the hug makes many people feel uncomfortable. All is a matter of personal space, insular Europe, for example, requiring more than continental Europe. |

|

Joints

Joints, like bridges (see "Bridges"), link here and there, but, in animals, not rigidly; they are points of articulation. In humans, the most obvious points of articulation, or joints, are the elbows and knees; also articulated are other parts of the body, such as fingers, thumbs and toes. Also articulated are head and torso, torso and arms, torso and abdomen, abdomen and legs, arms and hands, legs and feet. Adjectives associated with joints include sore and, with increasing age, arthritic.Other mammals have articulated joints, which is why one talks about a joint of beef, a joint of lamb, meaning a piece of beef or lamb containing a bone which once served as a point of articulation for the living animal and is now intended to be roasted and eaten by humans. Other living beings have members that can be articulated, but one does not talk of a *joint of chicken or a *joint of salmon, although they both have articulating bones.

Among other uses of the word is that of the marijuana equivalent of the tobacco cigarette. In the film Withnail and I, there is an example of an outsize joint, that of the wondrous, descriptive Camberwell carrot.

I shall also mention the joint as a place of dubious character - club, pub, café or restaurant - one notch above a dive.

Typing

In my first year at the Université de Besançon, I taught English from 8 in the morning until noon, then from 2 to 4 in the afternoon, after which, from 4 until 7 p.m., I became a student taking the Certificat des laboratoires de langues. A requirement of the final report of one of the courses of the latter was that it be typed, a quite unusual thing at the time (1963-4), as essays and reports were normally handwritten.I had an uncle who worked for the Remington company and was thus able to acquire a typewriter at a reduced price. So, armed with machine and Pitman manual, I taught myself to type.

Manual typewriters were replaced, first by electric typewriters, then by word processors, then by keyboards attached directly to monitors and remotely, via a modem, to a mainframe computer and printer, and finally by personal computers with attached printers. By the early nineteen-eighties, I had followed, in Canada, every evolution. I had even bought a "personal computer" made in Toronto, which required two people to carry it, and used 8-inch floppy disks. In the summers of 1982 and 1983, I worked in Exeter with the help of a second-hand Adler manual typewriter. Back in Toronto I acquired a desktop personal computer (5¼-inch floppies) as soon as one became available; the disk size was reduced to 3½ inches, before being replaced entirely by various types of internal and external computer storage.

My typing now takes place on a laptop computer and a smartphone.

A peck of geese

The books of collective nouns, mainly of birds, by Lipton, Rhodes, Palin, Fanous and company give the word gaggle as the collective noun for geese on land. Seen from afar, I would agree, but close up geese become belligerent, necks outstretched, beaks snapping; they cease to be a gaggle and become more like a peck.A collective for young girls might be a giggle of girls. At one time I called the daughter of French friends and her friend les giggleuses.

I now see geese flying overhead in skeins. Skeins of geese are impressive, of swans are majestic, of ducks are simply funny. While ducks appear to be flying hell for leather to get from A to B, gulls seem to be sneering at them, showing off their effortless and graceful flying skills as they ride the air currents.

Taste

|

I have written in my "Early memories" of memorable tastes, from my mother's rice puddings to the sensory experience of a meal partaken in Morestel.

I mentioned a memorable Toulouse fish soup, as an example of delicious sea food, rather than speak of Cancale oysters, Mont-St-Michel moules marinière and langoustines, Pontorson, Maine or Halifax lobsters, West Bay crab, Llandewi Brefi mackerel. One thing I didn't mention specifically was cheese. I am partial to Somerset and Ontario Cheddar, hard cheeses from the Cantal region, soft cheeses made in Normandy, but my favourite cheese is Comté, from the high pastures of the Jura, in the East of France. During my first year in Besançon, I lodged with the Scherlers. M. Scherler was a retired cheese-maker, so for breakfast each day, my café au lait and baguette were accompanied by wedges of hard, nutty-flavoured Comté cheese, for which I quickly developed a taste. Made in huge wheels measuring some 60 or 70 centimetres in diameter, it is, fortunately, available throughout France, so I have bought, and savoured, Comté cheese in a variety of places, including a fromagerie in the capital of Comté cheese, Poligny, another in the Rue Mouffetard, in Paris, and the market in Châtillon-sur-Chalaronne. |

Two homes

|

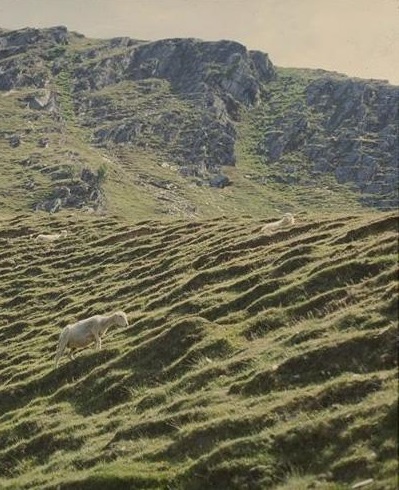

Inspired by the BBC programme Springwatch, I think back to the summers spent at my brother's in West Wales, which recharged my batteries for my return to the academic year in Toronto. I shall mention three particular aspects of these summers.

The greenness of the hillsides was marked by sheep and by fungi - field mushrooms and "magic mushrooms" in the open, boletus beneath the trees. To complete my Welsh bowl of breakfast cereal, I could simply go outside and pick blackberries* from the hedge. Sensory purity. In Toronto the university observatory has moved from the campus to Richmond Hill and thence to a mountaintop in South America; the night stillness was broken by the noise of air conditioners and ever-present traffic. In Wales I could clearly see the Milky Way by stepping outside my brother's hillside cottage and looking up at the night sky; at night the only sound was the occasional hoot of an owl or bleating of a sheep.

|

Tom Pierce

... lend me your grey mare. At grammar school I was influenced by several of the masters."Tom" Pierce was the Junior English Master. His classes involved more than just the English language and its literature. His passions included nature study, drawing and the composition of an annual quiz on Hampshire toponyms. At the front of the classroom was a specimen table containing leaves, flowers, perhaps even birds' eggs. To exhibit there one had to be able to provide a neatly written identification label. The sighting of a bird or mammal was written up in one's exercise book with identification, illustration and accompanying poetical expression. I once got 9/10 for my piece on a magpie, a proud achievement.

"Ponce" Cooksey was, along with "Tom" Pierce, a fearsome fives player and a paid Junior Classics Master. A school-friend and I lost to "Ponce" and "Tom" on the fives court, and I obtained high marks in O-level Latin and Greek thanks to the teaching of "Ponce".

"Fluebrush" Smith was a top chess player and a paid Senior French Master. At school "Fluebrush" introduced us to the songs of Georges Brassens. In France I worked one summer on the Marne farm belonging to his sister-in-law and husband.

"Oink" Griffin was the other Senior French Master. He took a group of us to Paris, where he wanted to show us the various locales of Balzac's Le Père Goriot, which we were studying at school, but his sense of direction was poor, so we ended up guiding him rather than the intended opposite.

"Whynot" Woodhouse. My favourite nickname. I never took classes with him. He was the chief editor of the Hampshire Chronicle, and made boys think for themselves ("Why not?").

"Doc" - Dr P.T. Freeman, MBE, BSc, PhD, FRIC, FZS, JP - was the Headmaster, a figure respected by all. He knew us all, referred to us individually as "brother" and collectively as "brethren".

In the end, it was "Fluebrush" and "Oink" who determined the direction of my further training and career.

Social cinema

Participatory cinema is well depicted in the Italian film Cinema Paradiso. I have experienced it in four locations.As a boy, I went one Saturday morning with cousins Jennifer and Pauline to the "threepenny dreadfuls" (price of admission = 3d) at the Maltby (Yorkshire West Riding) cinema. The audience comprised children only; the din was enormous. We sat near the front on the side and I remember the (distorted) lanky thinness of Hopalong Cassidy.

When I was in my teens, I worked one summer, along with schoolfriend Tony, on the farm run by school French master "Fluebrush" Smith's sister-in-law and husband in the Marne region hamlet of L'Échelle. On Saturday evenings, we would walk the two miles to the nearby town of Montmirail. There we went to the weekly cinema held in a converted barn. One arrived an hour before the projection of the film to greet one's neighbours and catch up on the local gossip. The "cinema seats" were benches, the "popcorn" was one's own homemade sandwiches made of chewy, huge pain de campagne slices with a pâté filling. The whole summer was one cultural shock after another for both of us; I was particularly pleased to be able to understand what was being said in the film we saw the second time.

In the 1960s, Kay and I had a similar experience in the Haute-Savoie town of L'Argentière-la-Bessée, where we had been hired by the aluminium company Pechiney to put the finishing English-language touches to eight foremen who were shortly off to install a new factory in the American state of Washington. Again, a converted barn; again, social gossip before the projection of the film.

Several years later I was attending a conference in the Canadian city of Halifax. In the evening I went out in search of a lobster restaurant. I came across a cinema showing the cult movie The Rocky Horror Picture Show, which for some time had been a permanent Saturday-night midnight fixture in the East End of Toronto, but which I hadn't seen. All I knew was that audience participation was a key element. I was easily the oldest member of that evening's packed showing. I sat at the back to see what would happen. At one point I realised that I was the only person sitting down - the rest of the audience was standing at the front, each person holding up a lit cigarette lighter. To use an expression of the time, it was a true happening.

Margoisms

A Margoism is a mixed proverb or other figure of speech as recounted on the lips of sister Margo by Gerald Durrell in the latter's books about his family's life in Corfu in the 1930s. Examples include: "there's many a slip without a stitch"; "there are no bricks without fire"; "It never rains, but it snows"; "she's trying to make a pig's poke out of a sow's ear"; "'They have a sort of ordure about them.' 'Don't you mean aura?' asked Larry."; "It's an eye for an ear"; "you might as well be hung for an ox as an ass"; "'She's got a lovely voice, Mother,' said Margo. 'It's a mezzotint.' 'Soprano,' said Lena coldly.".Some of these are what are sometimes called malapropisms. Christina Baker Kline puts a few Margoisms into the mouth of Flynn in The Way Life Should Be: "Beggars can't be picky"; "Is this going to put a cramp in my style?".

Lake District

|

The Lake District, which at the time of my visits occupied parts of the counties of Cumberland, Westmoreland and Lancashire, is now situated entirely in the county of Cumbria. I shall mention two particular visits.

In 1962-3, I was a student at Manchester University taking courses for the Graduate Certificate in Education. One of the extra options was Outdoor Activities, a practical course in camping, hiking, mapreading, rowing, canoeing and sailing, which took us, among other places, to Tatton Mere, the Isle of Arran and Coniston Water. Our campsite at the last-named was on the south-west bank. We sailed and canoed on the Water, and rowed one evening across to Brantwood, John Ruskin's last abode and, at the time of our visit, in the possession of Manchester University, for an illustrated lecture by the photographer of the 1953 Hillary-Tenzing Everest expedition. The most memorable part of the week was the camping-hiking-mapreading part. For this, we were split into two groups, the first going from the campsite to a designated spot on high ground several miles to the north. I was a member of the second group taken by car to the campsite of the first, and left to make our way back to base. As soon as the others had left, we quickly scrambled downhill to the pub. Several pints later, we painfully climbed back up to the campsite. In the tent we tried playing cards, but soon gave up, as the colour of the red suits (hearts and diamonds) disappeared in the murky light filtered through the canvas. The next day, the wind got up and the rain started. By evening the wind and rain were fierce, and we were unable to find a spot where we could drive in the tent pegs so that they would hold - the ground was either soggy or rock. There was no question of lighting a fire, so we ate cold baked beans and corned beef straight out of the tin. No question either of sleeping - it was all we could do to act as internal tent pegs in order to remain more or less dry. Exhausted and filthy, we tumbled thankfully into the pub in Coniston, where we consumed pints of the local draught bitter, and wolfed down pork pies and chutney. The second visit took place in 1977 and was a lot more comfortable. Ursula, Peter, Kay, I and our six children rented a cottage for a week in Appleby. A beck ran past the cottage door, and was the daily site for minnow fishing. We walked on Hadrian's Wall, and visited Penrith several times, including going to a hands-on pottery (see photo). |

Road surfacing

The road leading from the parking lot of the place where I now live has been undergoing digging up and resurfacing. I am reminded of the road where I grew up.Up until I was about twelve, the road where I grew up was an unsurfaced cul-de-sac just outside the limits of the municipality of Southampton, on the edge of the countryside. Beyond the barbed-wire fence at the bottom of the road were fields, farms, a gravel pit, country lanes, the distant puffs of smoke emanating from the train travelling between Romsey and Totton, and the minnow stream which ran into the River Test. The bomb shelters of World War II had disappeared, but the pot-holed road still had two gas lampposts.

Then all changed. The municipality expanded, cesspits were replaced by sewers, the fields started disappearing under the houses and roads of the new council estate, including the extension to my street. It became necessary therefore to macadam the road and make distinct pavements. I was then in my early teens. Wanting to be part of this brave new world, I volunteered my services to the team of workmen making the new road. I remember my particular task of digging a hole to install a drain. One day when I was at the bottom of the hole, a neighbour asked me: "Russon, what are you doing down that hole?"

Language learning: immersion and enjoyment

This is purely subjective, based on my own experience learning French. When asked, I reply: "I studied French at school, and learned it in France."Regardless of time and technology, of the four recognised language skills three are predominantly solitary activities: listening, reading and writing. Only speaking (plus listening to understand) is predominantly social (the telephone being a poor substitute).

Immersion can be artificial or natural. The classroom is artificial, a place for the imparting of knowledge, the learning of analytical and communication skills, and a (poor) medium for the simulation of social skills. Public spaces, such as shops and eating/drinking establishments, and domestic spaces (homes) are natural learning/practice places.

The classroom can immerse artificially, second-language public and domestic spaces immerse naturally, and are thereby superior.

Enjoyable learning is more effective than forced learning. Enjoyable activities include the cinema, watching television, games, affective relationships (apprendre sur l'oreiller, cf. "pillow talk"). It helps to like nature and native cuisine and culture; in other words, to enjoy the place where the second language is spoken as a first language. It helps to want to dream, and be able convincingly to swear and tell jokes in the second language.

Boat rides

|

I have always enjoyed boat rides, particularly the cooling breeze in summer and the wonderful vistas of islands or mainland.

When I was a boy, we often took the ferry to Cowes or Ryde in the Isle off Wight, or, boy or man, the ferry linking Southampton to Hythe (see first photo). At grammar school, naval cadets trips included: speed trials in the North Sea on a cruiser; participation in the Spithead Review aboard an aircraft carrier; and, most memorably, sailing from Bristol around Land's End to Plymouth on a frigate. Less enjoyably, I crossed the Channel several times to France (or Belgium), time enough to get seasick but not to find my sea legs. The most enjoyable and prettiest crossing was from Poole in Dorset to Saint-Malo in Brittany. When Kay and I emigrated to Canada on the RMS Empress of England (see second photo), I was pleased to find my sea legs after crossing the Irish Sea. The hurricane tailwind we passed through, and subsequent pitching and tossing, made for much amusement during the table-tennis tournament. Memorable boat trips I have taken include: from Vancouver to Vancouver Island; a boat trip around Manhattan Island; another from the south of Big Island, Hawaii to where the fire of the lava flows meets the cold water of the Pacific Ocean; a conference trip from Cannes to the Îles de Lérins; another conference trip, attended by a pod of dolphins, in the Galician Ría de Arousa. In Ontario: through the Thousand Islands region in the Saint Lawrence near Kingston; in a glass-bottom boat from Tobermory to see the shipwrecks in Fathom Five National Marine Park and thence round Flowerpot Island; from the lake at Inverlochy Resort, near Nobel, to Georgian Bay. Perhaps the most enjoyable boat trip I have taken was the one from Helsinki to Stockholm, passing through the many Baltic small islands which hug the Finnish coast.

|

Newspaper delivery

From the age of thirteen to that of nineteen I was a newspaper boy. This meant waking at six o'clock in the morning to a cup of tea made by my father, cycling to the newsagent's, sorting out the right number of each daily (Times, Daily Telegraph, Daily Express, Daily Mail, Daily Mirror, Daily Herald, News Chronicle, etc.) to be delivered, putting them in my shoulder bag, and pushing them through the appropriate letterbox (an English letterbox is in fact a slot in the front door). An important stop was in the sheltered hallway of a block of flats to read the headlines and sports pages. Then home for a quick breakfast, bus from Maybush Corner to the Central Station, and 8:25 a.m. train to school in Winchester. Each copy had about 20 pages, including advertisements, all in a single section.I now live in a small town in Ontario, and have a 51-year-old friend who delivers newspapers. She gets in her car at 1 a.m., picks up the newspapers at 1:30, and delivers them from 2 to 6 a.m. Each copy has multiple sections (they are far too thick to be pushed through letterboxes), a large number of ads, and ends up on a front porch or in an apartment lobby.

Autres temps, autres mœurs; times change.

Incomers, blow-ins and come-from-aways

Someone who has recently come to live in a particular place or area is typically called an incomer in England, a blow-in in Ireland, a come-from-away in Newfoundland. The three terms imply the arrival of an outsider in a more-or-less settled community and could hardly be used in London or Toronto, probably not in Dublin either. The terms make sense in a rural or isolated locality, little in a large urban one. In a wider - spatial and temporal - sense, the vast majority of people living in Canada (or, indeed, in North and South America) are incomers, blow-ins, come-from-aways.Harvest home

In Ronald Blythe's Akenfield, a Suffolk farmer tells the author that in the 1920s reapers had a daily allowance of 17 pints of home-brewed beer; when all the harvest was in, the harvesters enjoyed a horkey supper, with lots of roasted meat (beef, mutton), plum pudding and beer, all provided by the farmer.In my non-farming English youth, the celebrations took place in church, with the main event being the harvest festival at which hymns such as "Come, ye thankful people, come, Raise the song of harvest home" were sung in place of actual harvesting. The church would be decorated with wheat sheaves, plaited loaves, vegetables and fruit (I particularly remember the beautiful display in the church at Dedham). The eventual (church-organised) harvest supper would be but a pale imitation of the old horkey supper, with tea or lemonade replacing the beer.

In Canada, harvest home is typically celebrated neither in the field nor in church, but around the (extended) family dining table. In fact, Thanksgiving Day, the second Monday in October, is less about giving thanks for the harvest than about consuming roast turkey and pumpkin pie. This guzzling often takes place not on Thanksgiving Day but on the preceding Sunday or Saturday, so that the cook can use the following day or days to recover before resuming normal life.

The fish plate

With a nod to Annie Proulx (Accordeon Crimes) and François Girard (Le Violon rouge).At Christmas 1961, Janine, to whom I was engaged at the time, gave my parents a beautiful oval earthenware salmon plate made by a French potter. Although I didn't marry Janine, I continued to admire the plate.

Many years later, after my parents had died, my eyes were drawn to the plate, affixed to the kitchen wall, each time I visited my brother's home in West Wales.

My brother died a number of years ago. The plate is probably now admired, perhaps used, by one of his children. (I hope.)

Imperial measures of distance

In my English school years (1944-58), I learned, and used, the following distance measures. 12 inches (12") = 1 foot; 3 feet (3') = 1 yard; 22 yds = 1 chain (length of a cricket pitch); 10 chains = 1 furlong (horse-racing term); 8 furlongs = 1 mile. Or, 5280 ft and also 1760 yds = 1 mile. Feet were measures of both horizontal and vertical distance, yards and miles horizontal only. In the naval cadets I learned the maritime measures of the fathom (6 vertical feet) and knot (the speed needed to cover one nautical mile; 1 nautical mile = approximately 1.15 statute or terrestrial miles). Leagues (1 league = 3 miles) were the stuff of fairy tales; rod, pole and perch were strictly surveying terms, acres of interest only to farmers.Britain, like Canada, has since adopted metric measures, but it will take several generations for some terms of metric measurement to become meaningful. Britain has retained the mile on road signs to mark the distance between A and B; Britain and Canada still serve draught beer in imperial pints. Some imperial terms have a concrete existence: lots of land and the rooms of a house are, for many Britons and Canadians, measured and conceived in feet; the word kilometrage has yet to replace mileage (and cf. "to get mileage out of something"). The 100 metres has replaced the 100 yards in athletics (and similarly with longer distances), but cricket pitches are still measured in yards, horse races in furlongs.

Idiomatic expressions, always resistant to change, include: "to within an inch of one's life", "to come within an inch of", "to die by inches", "to miss by inches", "give an inch and he'll/she'll/they'll take a mile", "to be miles away", "to miss by miles", "to go the extra mile", "to talk a mile a minute", "to stand out a mile", "a country mile", etc.

Vous, tu, crow and fox

In Canadian immersion French, the word tu has to serve as both singular and plural pronoun. In theory, students know about the existence of vous, but don't know how to use it, especially since modern English makes no pronominal distinction between second-person singular and plural, nor between formal and informal second person. I lived in France, where vous is both second-person plural and formal singular (cf. Spanish formal usted/ustedes vs. informal tú/vosotros). This resulted in the absurd situation of my addressing my university students individually as vous, they addressing me as tu.During a sabbatical leave in France, my son, who attended the local lycée, was talking one day on the phone in impeccable school French to the mother of one of his class-mates. He asked her "Est-ce que tu sais si Thomas s'ra là c't aprè'm?". When he had finished the call, I told him that he should have addressed her in correct French: "Est-ce que vous savez si Thomas sera là cet après-midi?". When I recounted this to my Canadian students, one of them asked me when he would have able to address her as tu. My answer - probably never - was met with unbelieving gasps from all.

The switch from vous to tu in addressing the same person is quite possible in France but implies that the two correspondents can become equals; it also represents a key psychological moment. One of the best examples of this occurs in a cinematic adaptation of the fable of the crow and the fox.

In the seventeenth century, Jean de La Fontaine wrote a series of fables, well-known throughout the world, the best-known probably being Le corbeau et le renard.

-

Maître Corbeau, sur un arbre perché,

Tenait en son bec un fromage.

Maître Renard, par l'odeur alléché,

Lui tint à peu près ce langage ...

In 1966, Hervé Bromberger directed a film starring Michel Serrault as Maître Corbeau, Jean Poiret as M. Renard and Anna Karina as Mme Corbeau, the coveted cheese. The film, true to the fable, is a satire of human vanity and the false admiration of flattery. M. Renard, a mechanic by trade, is infatuated by the occasional glimpses at her window of Mme Corbeau, jealously kept at home by her husband. One day, Renard finds himself in court on a charge of a minor infraction of the law. To his delighted surprise, the prosecuting counsel is none other than Maître Corbeau (in France, lawyers - avocats/avocates - are addressed, both professionally and socially, as maître, whether they be male or female, just as in English eminent musicians, especially conductors, are addressed as maestro). Great is the astonishment of Maître Corbeau at the end of his peroration to see the accused, Renard, give him a Gallic gesture of approval (like a "thumbs up"). Even greater is his astonishment when Renard shows him a gesture of disapproval (a "thumbs down") at the end of that of the defence counsel.

Subsequently Renard courts Maître Corbeau, making sure to be the loser of their games of tennis. He is overjoyed the day Maître Corbeau addresses him as tu; stage one of the conquest has been accomplished. In the fable, Maître Renard praises the beautiful plumage of Maître Corbeau and his beautiful singing voice (inviting him to open his beak in song - and drop the cheese); in the film, Maître Corbeau's pride and joy is his hunting horn. The film ends with a triangular picnic where Renard persuades Maître Corbeau to entertain them with a flourish of his horn from the top of a distant hillock while he is left to enjoy the delectable cheese.

Interesting roads

|

The modern road, allowing one to get from A to B, has straightened out the winding lane of yesteryear, has proliferated to match growing populations, and gradually lost its local focus and interest.

There is, on the other hand, the mythical road, that portrayed in Gabrielle Roy's La Route d'Altamont, one she drove on in Manitoba with her mother, that appeared magical at the time, but which she was unable to find again. The nearest I have come to that is the present near impossibility of finding, between the Midlands and Lancashire, the unencumbered A roads of yore, replaced, as many of them are, by the motorways on which one almost inevitably ends up, only to be caught in traffic gridlock. At least, that seems to be the case with the M6. No magic there. Magical, however, are the lanes in West Wales leading from Llandewi Brefi to the A482 near Ffarmers, by way of a hedgehog crossing, a ford and a Roman road, with the hedges brushing the car on either side. Before the days of the sat nav, or GPS, as it is called in North America, all drivers relied on maps. The best in Britain are generally reckoned to be those published by the Ordnance Survey. I have thus discovered a grassy lane in East Anglia, ending up in a field. I came upon a similar road in the foothills of the Rockies, a small road leading, according to the map, to the Icefields Parkway, but petering out, in fact, a few miles short of the highway. The map was out of date. |

Regional festivals

The feast of St. Nicholas, celebrated on 6 December, is celebrated in various parts of Europe; the figure of St. Nicholas has given rise in North America, via Holland's Sinterklaas, to the figure of Santa Claus. I attended a St. Nicholas parade in Nancy, in the East of France.Again, in the East of France, but in Lorraine's neighbouring province of Alsace, I attended a feu de la Saint-Jean on the night preceding the feast of St John the Baptist, 24 June and intended to mark the summer solstice.

As a boy I attended several Whit walks in Maltby, in the West Riding of Yorkshire. These were church and chapel parades, which took place at Whitsun (seven weeks after Easter), and involving congregation members, brass bands, banners and hymns.

Carpets and fields

An outdoor carpet is an unbounded area, whereas a field is limited by markers such as hedges, stone walls or fences.

Thus, one may encounter a carpet of daffodils or of bluebells or of snowdrops, for example, such as the carpets of daffodils I have seen in Wales or north of Bath, those of bluebells seen at the eastern edge of the Cambrian Pass in Wales (photo 1), near Stratford St Mary in Essex, at Ashley in Hampshire, that of snowdrops in the churchyard of Felbrigg in Norfolk (photo 2).

I remember the fields of lavender in Provence (photo 3), the fields of sunflowers in Languedoc (photo 4).

Apple picking

|

When I was a boy, a gang of us picked apples in the orchard of a nearby house. We did it stealthily, not having asked permission to climb the trees. It was considered a normal activity for growing boys, and was euphemistically called "scrumping".

As a responsible adult living in Canada, I organised parties for my children and their friends. At one, the children had to bob for apples (photo 1). The apples used in this game had been picked at Chudleigh's, then a simple rural apple farm north of the small community of Milton. At that time, one could climb up into the branches of the tree (photo 2), whereas now apple trees tend to be severely pruned into unclimbable two-dimensional espaliers. |

|

Two homes (2)

|

When I was an undergraduate, I had a principal home at my parents' and a secondary one in Manchester. Similarly, when I was living in Toronto, I had my main home there and a summer one at my parents' in Hampshire. When I visited my brother in Wales, I had a second home there (see "Two homes").

Now my eldest daughter has her own apartment in Toronto and a second home, my second bedroom, which only she uses, when she comes to visit me. My father turned his garden shed into a playhouse for my youngest daughter and her cousin by the simple expedient of sawing the door in two to create a half door, similar to a stable door (see photo). Being able to keep, and refind, certain personal belongings in one's second home is the source of a special warm feeling. It is similar to the one that North Americans experience when they go to "the cottage". |

Portal of the year

In science fiction and fantasy, a portal is a doorway or gateway connecting two contrasting parallel worlds, such as the doorway which allows Alice to enter Wonderland or the ancient Gaelic threshold festival of Samhain, which has been replaced in the churches of Christianity by that of All Hallows, the meeting of the living and the dead.

In North America particularly the Eve of All Hallows (31 October) is better known as Hallowe'en, marked in the present day by hollowed-out pumpkins (photos 1-3), in place of the turnip jack-o'-lanterns of yore, trick-or-treating, and houses and gardens adorned with skeletons, ghosts and tombstones.

A more ancient custom can be observed in certain regions of Mexico, where the dead are celebrated on the two days of the Día de los muertos (1 and 2 November) and the intervening Noche de los muertos, spent in cemeteries around the graves of loved ones. During the build-up to the festival, shrines, giving prominence to marigolds, a symbol of death, are erected in courtyards and on roadways (photo 4). The marriage of life and death is supremely represented by the catrinas, girls and young women dressed in sumptuous gowns with their faces made up to look like skulls (photo 5).

Bonfire Night

-

Remember, remember, the fifth of November,

Gunpowder, treason and plot.

The custom, also called Guy Fawkes Night, which has lasted four centuries, is to burn an effigy, called "the guy", representing either the leader of the plot, Guy Fawkes, or the pope. Guy Fawkes himself was not burned at the stake, but, just as gruesomely, hung, drawn and quartered. In my boyhood, the effigy was paraded around to the appeal "penny for the guy", the resulting pennies spent on fireworks, the other principal component of Bonfire Night.

Fireworks - roman candles, rockets, Catherine wheels, bangers and jumping jacks - were readily available in newsagents', and could be bought indiscriminately by adults and children, mainly boys. Bonfire Night was a neighbourhood event, particularly after the War, but the fireworks, particularly bangers and jumping jacks, were accumalated and set off any time before or after the main event.

I remember an impromptu firework display in my grammar school class, second year. The class clown, Martin Smee, was unable to stop himself furtively lighting a jumping jack inside his desk during class! Each time the firework exploded a puff of smoke would rise up in the air through the inkwell hole, while the desk lid banged. The master, "Biffer" Smith, wisely allowed the show to continue, to the hoots of glee of all the boys except one, waiting until all was over before confiscating the foreign contents of the desk, and imposing several detentions on the hapless Smee.