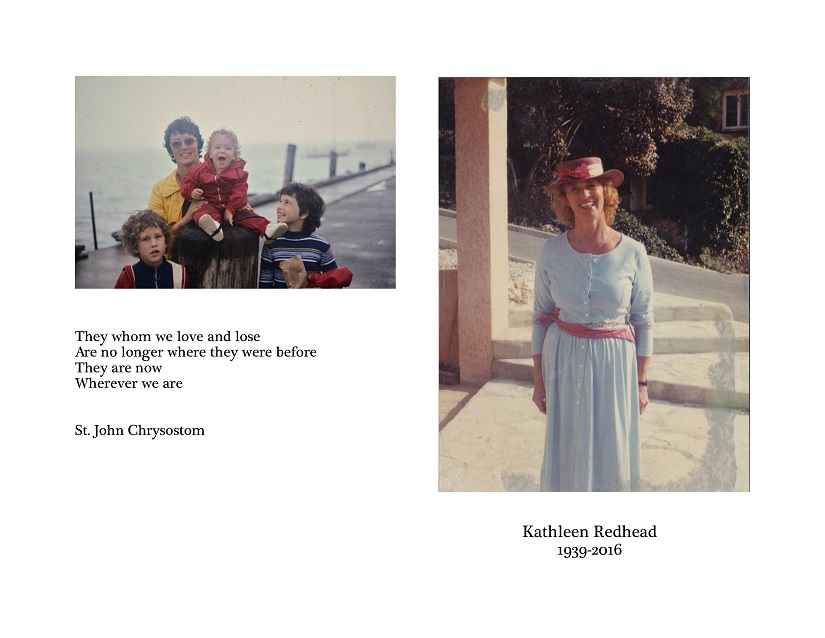

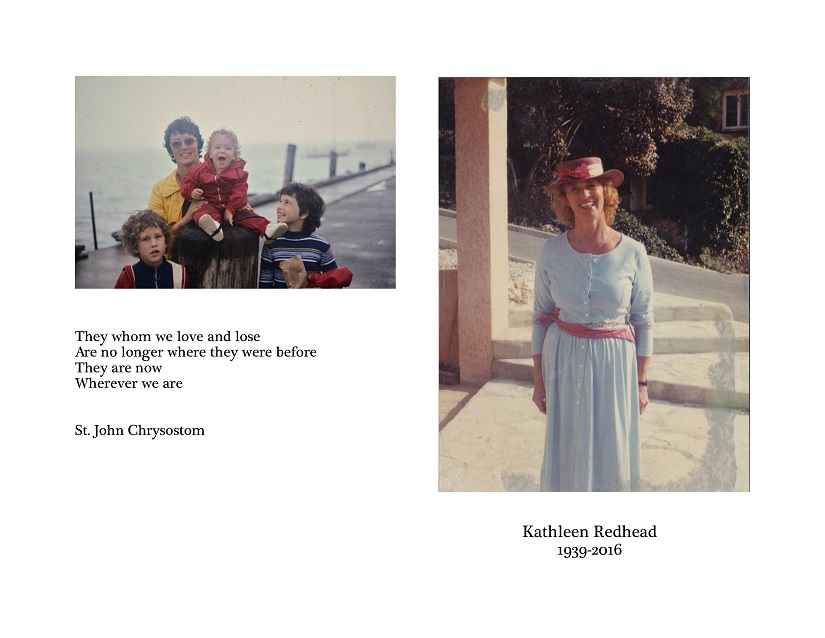

A celebration of her life

Catherine, daughter

“All will be well, all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well”

My Mum used to say these soothing and reassuring words to me to calm my fears and worries starting when I was quite young. It was only when I studied T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets that I learned a bit more about the woman who wrote them: Dame Julian of Norwich: an English mystic, theologian, and anchoress, who is celebrated for her optimism and courage throughout her grave illness and many other trials. She became known in her community as a wise counsellor who combined spiritual insight with common sense, and her teachings are still widely read.

It is a credo that I have tried to carry with me my whole life, almost like a type of spiritual worry bead, not least because it encapsulated Mum’s approach to life, but also because it gave me a special link to her.

Mum was a gardener, a cat-lover, a writer, a translator, a poet, a traveler, a dancer, an eternal optimist. She made friends wherever she went. She was always up for a spontaneous adventure.

She had the unique ability to extract joy out of an ephemeral moment: seeing a butterfly land on her Michaelmas daisies; watching her beloved cat Blue stretch and roll in a sunbeam; eating a forbidden Kit Kat and hiding it under her pillow after major surgery; having a picnic in the park in January.

As our mother, Mum turned everything into a game. She let us create our own gardens and choose what we planted, often flowers and vegetables in the same patch. Carrots and Bachelor’s Buttons grew side by side, to our great delight.

When I was six I caught chicken pox one hot and sticky July, and they covered my body completely. I couldn’t bear anything touching my skin and desperately wanted to scratch away the itchiness. Mum sat and read aloud The Wizard of Oz to me over three days while I lay in my bed, transported into Dorothy’s journey, far away from my itchy spots.

When we lived in England and were homesick for our friends back in Canada, she would take us to the sea instead of school, calling it a “mental health day”. We sang songs in the car and played games spotting animals and styles of architecture, naming clouds, and tallying license plates.

Mum, however, was a nervous driver, and any noise or silliness in the back was met with a stern “Put your knee forward to be pinched” or “Put both your hands on the window”. We did, strangely obedient to her strict yet hypnotic commands. Drivers in the lanes next to us would pass us with mouths agape.

She delighted in embarrassing me as a child - she’d dance in the street, grab my hand and force a twirl; conduct classical music as she drove me to high school - I’d ask to be let out a couple of blocks from the school so no one would see me with her.

Mum shared her taste for words and literature with us as children. She recited to us lines of poetry that spoke to her, words we could taste, or see, or feel. Keats, Yeats, Wordsworth, Seamus Heaney, Mary Oliver, and of course Shakespeare. It forged a strong bond between us that continued into my adulthood; we often had hours-long conversations about books and ideas, reading aloud our favourite poems or lines of prose.

Mum’s unrelentingly positive outlook; her ability to weather the most difficult hardships and turns of fortune; her gift for reinvention and resourcefulness - all of these qualities emerged when she was nine. Her kind, compassionate, gregarious and loving personality hid a core of steel, forged in the crucible of her year-long hospital stay. She was allowed adult family visitors only once a month for two hours.

She was encased in a body cast that made it impossible to sit up. She went outside only once the entire duration of her time there - a trip to the sea, where she was carried out of the bus and laid down on the sand like a beached seal, soaking up the warmth of the sun, hearing the birds, and feeling the wind and fresh air on her skin. She refused to sink, refused to be medicalized and institutionalized; and instead held onto her true, precious self - a brave, strong little girl who had to learn to walk again once she was discharged. She only told us about this time when I was in my twenties, and I knew then that her resilience and fierce independence had been hard earned.

Mum embraced unconventionality and savoured others’ reactions when she did or said the unexpected. Speaking truth and staying true to herself were vital to her. A born-again atheist, she once wrote a letter to the editor of the local paper protesting an editorial which she considered to be Christian proselytizing and thus unacceptable. After her letter was published, she received many anonymous phone calls from well-wishers who said that they were praying for her. I told her just to hang up, but she insisted on talking to them. A few of them hung up on her.

Only Mum could go on a 50 year “un-anniversary” trip with Dad to Ireland, where they had spent their honeymoon. I turned on the BBC news, expecting the newsreader to lead with “Hostilities have resumed in Ireland after two decades of peace”. My fears were unfounded, however. They had a brilliant time and came back full of stories, well-rested and invigorated. Mind you, these are two people who moved across the hall from each other after over 20 years of divorce, and ate dinner together every night.

There is so much more I could say about this incredible woman. She has left us a remarkable legacy: her poetry and writings; a love of music and language that she has passed on not only to her children but also to her grandsons; but most importantly, her indomitable spirit and generosity and empathy; her strength and courage and infinite adaptability; and her wonderful and wicked sense of humour.

I’ll end by sharing this morsel with you, so you can see for yourselves:

GRAFFITI

The walls of my mind

Are covered with graffiti

Some of it is nice

But some is not so pretty

Sarah, daughter: reading one of her Mum's poems

|

ADVICE

Take the train

Dye your hair

Lose some weight

Get a job

Go to bed

Take a ride

Fix your hair

Grow your nails

Clean your teeth

Go to school

Smarten up

On your bike

Disappear

Bugger off

Take a trip

Fly a kite

Take a plane

Cut your hair

Close your mouth

Stay at home

Go to hell

Take a hike

Paint your nails

Bag your head

|

Catherine, reading one of her Mum's poems

|

THE JOURNEY 4

Today I drove the length

And breadth of my life

Remembering other lives

Flavoured by time and times

The weather kept pace

With my clear-blue thoughts

It etched out the dawn landscape

But by noon the clouds formed

Cirro-cumulus

Windswept and woolly

Overlay the noon-time-ridge

And later the rain came

Then there was a rainbow

That unasked gift of

Colours that sets us seeking

For the usual pot of gold.

The sky-lakes gleamed, as yet

Unnamed and unexplored,

Silver and azure, as they were

When I was very young and simple.

|

Russ Wooldridge, ex-husband and lifelong friend

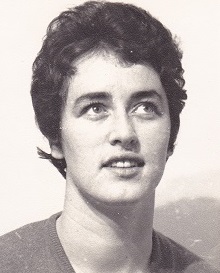

Kay's student days

I met Kay when we studied French at Manchester University, both of us in the same year. The aim of a lot of students was to get as far away from home as possible and learn to grow up. I was from the South of England, Manchester is in the North. The parties at Kay's Catholic parents' home in Wilmslow, just south of Manchester, were a revelation to me, a raw boy from a teetotal Methodist home. Mr and Mrs Redhead sat chatting to the students, and the beer was served by two charming little girls, Kay's younger sisters, Julie and Elizabeth.

I met Kay when we studied French at Manchester University, both of us in the same year. The aim of a lot of students was to get as far away from home as possible and learn to grow up. I was from the South of England, Manchester is in the North. The parties at Kay's Catholic parents' home in Wilmslow, just south of Manchester, were a revelation to me, a raw boy from a teetotal Methodist home. Mr and Mrs Redhead sat chatting to the students, and the beer was served by two charming little girls, Kay's younger sisters, Julie and Elizabeth.

At the end of our second year, we spent the summer term abroad in the South of France, I in Montpeller, Kay in Aix-en-Provence. My 21st birthday, the age of majority at that time, was celebrated on the beach at Palavas-les-Flots near Montpellier, attended by students from Manchester, Sheffield and Birmingham, and Kay and her room-mate, who hitched over from Aix. We spent the night on the beach, and the next morning went for café au lait and croissants at a nearby café, where Kay and I danced bare-foot to Edith Piaf singing "Milord".

While Kay did her third year of French, I spent the year at a lycée in Normandy working as an English assistant. I wrote to Kay, who read out my letters for the general amusement and edification of our class-mates.

I returned to Manchester, and we graduated together at the end of the year, Kay with a double honours BA in French and Italian, I in honours French. After the first two weeks of finals we went to the last day of the Didsbury tennis tournament, where we watched a charming pair of 18-year-olds, Billie Jean Moffitt and Karen Susman, win the final of the ladies' doubles. An itinerant newspaper-seller was calling out "Read all abaht it - Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton"; a nearby wit commented "I didn't know they were in the mixed doubles".

I wanted to stay on in Manchester, so I enrolled in the Graduate Certificate of Education course. Kay spent the year teaching English, Arithmetic and Social Studies to day-release students at Salford Tech, in the "Coronation Street" part of Manchester. Her students were good at subtraction, through playing 501 at darts, but otherwise were hopeless at arithmetic. A lot of them sat with their transistor radios glued to their ears, listening to the racing results.

Then Kay spent a year at the University of Toronto, doing an MA in Italian, while I went to Besançon, in the East of France, to do graduate studies. We wrote to each other throughout the year and got engaged at the beginning of the summer. We bought the engagement ring in the Portobello Road market in London.  The wedding took place in Wilmslow at the end of the summer. The fastest route to the church from the guest-house where my best man, Barry, and I changed was through Woolworth's. So, in our top-hats and tails, we treated the sales-girls to a show.

The wedding took place in Wilmslow at the end of the summer. The fastest route to the church from the guest-house where my best man, Barry, and I changed was through Woolworth's. So, in our top-hats and tails, we treated the sales-girls to a show.

We spent our honeymoon in Connemara, in the West of Ireland. There we lost track of time, and when we walked to the shop, three miles away, we greeted everyone we met with a "Good morning", and were wished a "Good morning" in return. It was only when we reached the shop that we found out it was the middle of the afternoon. The nearest town was Clifden, nine miles from our cottage. We were assured that the first car that passed us would pick us up. We walked the first eight before encountering a car.

One evening, sitting in front of our peat fire at our cottage, Kay did her "zombie" ("Nanny Nollips") impression, in which she tucked up her dried lips and eyelids, so that her teeth and eyes dominated her face. I was duly terrified, a condition made worse by the appearance at our door of a lamp-bearing, hooded figure in black, who turned out to be our landlady Mrs O'Donnell come to bring us potatoes and onions. Kay had doubtless developed the character at her convent boarding school to scare the other girls in the dormitory, a trick similar to the ghost-story one I participated in at scout camp (one morning a dew-drenched Robert Smith was found in his sleeping-bag having wriggled out under the tent flaps).

We then spent the first two years of our marriage in Besançon, undertaking linguistic studies and teaching spoken English in six-week intensive courses. We teachers didn't have much money, whereas our students - including civil servants, government ministers, air hostesses, pilots, hoteliers, doctors, dentists and a newspaper editor - tended to be well-off. They, being French, wanted to explore the regional gastronomy, so we were invited out for a lot of meals. The intensive nature of the course brought with it whirlwind romances, firm friendships (and enmities), laughter, tears and dreams in English. There was inevitably an end-of-course party, and presents for the teacher. During our two-year stay, Kay received three Hermès silk scarves.

During our time in France, we were invited to stay in Palermo by one of Kay's students, the wife of a member of the Sicilian parliament. Highlights of the trip included, in Rome, being taken out dinner by the subject of Kay's MA and future PhD studies, the poet Giuseppe Ungaretti.

We emigrated to Canada in 1966, sailing from Liverpool to Montreal on the Empress of England. We went twice to Expo 67 in Montreal. On the way home after our second trip, Kay felt nauseous and subsequently found out that she was pregnant with our first child, who turned out to be Catherine.

Two years ago Kay had the idea of our returning to Ireland to celebrate fifty years of marriage-and-divorce.

The shuttle-bus driver taking us from the terminal at Dublin airport to the car rental treated us to some expressive English, such as "Take it easy but hurry up". Kay never took it easy. Fellow student, marriage partner, co-parent, ex-wife, she was always my very good and true friend.

From Elizabeth Thomas, Kay’s youngest sister

Kay was a thoroughly likable person - no-one could meet her and not immediately warm to her good-heartedness and lovely spirit.

Kay had a zest for life and enjoyed every day. She was intelligent, kind, friendly, compassionate and took a great interest in everyone and everything - full of the joy of life!

She kept close to all her family so that each felt special to her. Kay was a Guardian Angel to her little sisters who have delightful memories of her. She was truly A Woman Not To Be Trifled With and taught her little sisters to be so. They in turn have passed this on to their own daughters!

All her nieces and nephews have a place in her heart and felt loved by her.

The Marvellous Woman - Bless her - is now flying free!

From James Thomas, Kay’s nephew and Elizabeth’s son

A wonderful Auntie, so wise and full of great stories and good advice. She always had time for each of us, and had the ability to make everyone she spoke to feel very special.

Every time we had a chat, whether in person or via a long-distance telephone line, I always felt an incredible connection with her. She seemed to just know what you were feeling, and would always say the right thing.

She is very much missed, and the connection between her and all of us remains. I love you Auntie Kay.

From Carole King, Kay’s elder sister

Kay was known in every sphere for her resilience. However she and I were very sad not to see or talk to each other for a whole year. She was suddenly in hospital and I in boarding school - in opposite directions from our home by the sea.

And then our connection and deep friendship was of course sealed when we were then together at Lark Hill.

As writers we are each other's editors.

We talked for hours every week and put the world to rights. Our love of languages and travel brought us sharing joy. Gardening was dear to both of us as to our Mummy.

Best of all we laughed a lot together and could see the sense of the ridiculous as well as the fun side. Wonderful girl.

From Kirsten King, Kay’s niece and Carole’s daughter

Kay was always kind and loving to me, full of fun and smiles. Her strength to be brave at all times any time was always amazing to me. Carry on and carry through.

I knew her all my life as my Aunt and my Godmother and my friend, and will truly miss her dearly. Love you Kay.

Vince, husband of Sarah: reading one of Kay's poems

|

TEMPORAL

Lose no time

Time is money

And time and tide

Wait for no man

There’ll be no time

To search for lost time

It’ll take all your time

To find the time

And only time will tell

If it was all

A waste of time

Time being money

For the time being

It would be timely

To save time, to

Spend your time well

Put the time in

To take time out

From time to time

And be careful

When passing time

That time does not

Pass you

Remember

That time past

And time present

Are both contained

In time future

And how you use

Your time will be

How time uses you

The best time may not

Be the first time

Nor the last time

The worst time

If there’s any time left

It could be the right time

|

(From Kay Redhead, The Song of the Artichoke Lover, Hamilton, Mekler & Deahl, 1996)

Sandra and David, friends

Sandra last spoke to Kay on the telephone two or three months ago, but nothing suggested that this would be our last time. That our last contact was by telephone is only fitting. We have both known Kay since our first arrival in Canada, in 1967. Coming from modest backgrounds in England, the telephone had always seemed something of a luxury, particularly since all local calls were charged by length of call. For us Kay was always Queen Telephone. She taught us how, when local calls were free, the telephone could work like the backyard fence of our childhoods. It extended sociability beyond the family circle. In Japan, apparently, three refusals of a second cup of tea were required to be taken seriously. For Kay, at least three rounds of “I won’t be keeping you, then” were required to wind those conversations down.

So our earliest memories of Kay go back to our first arrival in Canada in 1967. Back then, the Department of French at U of T made numerous appointments every year. We were joining the French Department in University College, in the Faculty of Arts and Science at the University of Toronto. As I recall it, there were parties to welcome new faculty members at every level. This would be repeated at Christmas, and again at the end of the academic year in April. And so for us Toronto seemed like the city of constant welcomes. Amongst the colleagues welcoming us was Kay, one of the mums-to-be discussing breathing techniques and epidurals in one corner of all these parties. But even though we were not at all pregnant, Kay soon invited us to her own welcomes on Kendal Avenue. Then when all these new mums were discussing diaper services and sleep deprivation, Kay carried on reaching out to us. This really made a difference as we began a family of our own. And gradually our two families grew together.

I went off to work on my doctorate for a year in 1970-71. When we got back, we found that our landlord had reclaimed possession of our rental home, and we had nowhere to live; we were not even sure where our furniture and other belongings had been taken. Kay and her family took us in to their house on Elvina Gardens for as long as it took to find another house to rent. This turned out to be a rather grotty bungalow on Merton Street. I found our furniture in a distant warehouse, loaded it in a 16-feet van, set off and promptly stalled it in the intersection of Eglinton and Mount Pleasant at the beginning of rush hour. That was when the starter died and the traffic helicopters circled overhead, and we made the news on every local radio station. I arrived at the bungalow three hours later than expected. And there was Kay in old painting clothes with Sandra and they had actually painted the walls of both of the bedrooms and the place was beginning to look inhabitable.

Our memories of Kay and the family on Keewatin Avenue, are of Christmas Eves and Days shared among our two families. English Christmas meals consummately organized and prepared; carefully sequenced gift exchange unwrappings; and then after a round or two of Mille Bornes came the ceremonial listening to BBC radio comedy shows, Take It From Here and the Glum family, Hancock’s Half Hour, and so on. For me the most memorable time was the year of my buttock boil. For some reason, this flared up as we arrived for the celebrations and I had to say that I would probably have to remain standing for the whole time. Kay arranged cushions on a chair, so that my right buttock was cantilevered out. She phoned the on-call doctor for her family, and he actually came out. He spent his Christmas Day lancing my boil and giving me an antibiotic jab.

Kay may have been a lapsed Catholic, but she did introduced us, the lapsed Anglicans, to a post-Vatican II Midnight Mass and Christmas Day birthday party, complete with a nun in a bright floral frock playing a guitar, singing folk songs, and a big birthday cake with a myriad of candles, which all the children in the congregation helped blow out.

In 1976, we returned from a research leave to England. During those 6 months, Kay was our contact person with the lawyer administering the rental to two rather disreputable characters, one a leather goods salesperson, the other a tap dance instructor. Russ called them the “thong and dance” team. Most of their rent checks bounced. Kay accompanied our lawyer round to try to resolve things a week before our arrival. They found the birds had flown the coop and the house was a total mess. They had not paid the water bill and the water had been cut off, the toilets had not been flushed, the bath was full of what looked like swampwater. The whole of the living area was piled high with garbage and litter (including the unpaid water rate bill). Kay and Tom spent hours filling twenty large garbage bags with the mess, they cleaned the bathroom areas and later restored the water and electrical power. We arrived to find a dirty house, but one in which all the things did work and where you could actually see most of the floor.

Kay was also one of our guides to the south of France; I wrote part of my thesis in the early seventies sitting on a balcony high above the Var valley as the cicadas sang and the sun beat down. Kay plied me with the refreshments needed to ease the task before setting off with the others to the beach. Later we would discover Kay again beside the Mediterranean, this time as a teacher at the Universitè Canadienne en France near Nice, high above the corniches and the Bay of Angels, and regaled us with the stories of her beloved students. That was when we first heard her memories of artichokes, eventually published in her book of verse. In the 1990s, she would be a teacher helping organize our Summer ESL program for overseas students at New College. It was the very beginning of a program that has gone on to become one of the most successful in the whole university.

In ensuing years, we became her guests at her Wellington B and B. Not so full of bronzed naked bodies as the French Riviera, but enchantingly close to Lake Ontario; our little bedroom looked right on to the gently lapping water.

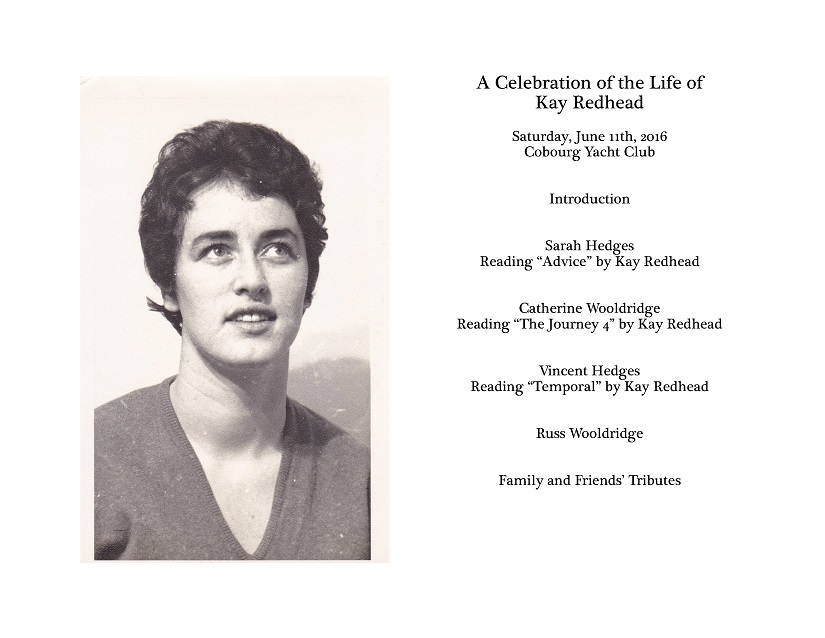

So many memories; so many conversations; so much fun; that Lancashire accent we had always associated with the comedians of our childhood years, Al Read, Ken Dodd, and Stanley Holloway. Unparalleled hospitality, a real friend in need so many times, a seemingly unfailing cheerful disposition. Kay was also an unimpeachable source of information about the misdeeds of our many colleagues in the appropriately named French Department, perhaps because she shared cleaning ladies with some of them. At the same time she was quite willing to denounce injustices in no uncertain terms, including the many that she herself encountered as a female member of faculty. But above all, her face that brightened into a broad smile (the photograph on the front of the memorial program captures her better than anything else.) as she recounted yet another irony of everyday life followed by the infectious laughter. That is the Kay we remember and love.

I met Kay when we studied French at Manchester University, both of us in the same year. The aim of a lot of students was to get as far away from home as possible and learn to grow up. I was from the South of England, Manchester is in the North. The parties at Kay's Catholic parents' home in Wilmslow, just south of Manchester, were a revelation to me, a raw boy from a teetotal Methodist home. Mr and Mrs Redhead sat chatting to the students, and the beer was served by two charming little girls, Kay's younger sisters, Julie and Elizabeth.

I met Kay when we studied French at Manchester University, both of us in the same year. The aim of a lot of students was to get as far away from home as possible and learn to grow up. I was from the South of England, Manchester is in the North. The parties at Kay's Catholic parents' home in Wilmslow, just south of Manchester, were a revelation to me, a raw boy from a teetotal Methodist home. Mr and Mrs Redhead sat chatting to the students, and the beer was served by two charming little girls, Kay's younger sisters, Julie and Elizabeth.

The wedding took place in Wilmslow at the end of the summer. The fastest route to the church from the guest-house where my best man, Barry, and I changed was through Woolworth's. So, in our top-hats and tails, we treated the sales-girls to a show.

The wedding took place in Wilmslow at the end of the summer. The fastest route to the church from the guest-house where my best man, Barry, and I changed was through Woolworth's. So, in our top-hats and tails, we treated the sales-girls to a show.